The first person who, having fenced off a plot of ground, took it into his head to say this is mine and found people simple enough to believe him, was the true founder of civil society. What crimes, wars, murders, what miseries and horrors would the human race have been spared by someone who, uprooting the stakes or filling in the ditch, had shouted to his fellow-men: Beware of listening to this imposter; you are lost if you forget that the fruits belong to all and the earth to no one!

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Second Discourse (Discourse on the Origin & Foundation of Equality)

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Masters, Roger and Judith, ISBN: 978-0312694401 (page references below are to this edition)

Scott, ISBN: 978-0226151311

The questions that prompt the Second Discourse are: What is the origin of inequality and is it authorized by the natural law?

Rousseau’s answer to the first is “political society” and to the second is “no.” He begins the Second Discourse by arguing that the state of nature is far from a Hobbesian Mad Max “war of all against all.” Rather it is the relatively peaceful, if occasionally punctuated by violence, life of the solitary animal—imagine Australopithecus, but solitary, or a lone Yeti-man. The rest of the First Part of the Second Discourse is largely Rousseau’s explanation of language and concept acquisition. In the Second Part, Rousseau begins laying out his complex political genealogy that acts as an explanation for the origin of inequality. Man in a state of nature slowly moves up the ladder of civilization by increasing his understanding, which in turn increase the scope of his passions, which in turn act as further needs to be satisfied by his ingenuity. As he increases his goods and virtues he increases his ills and vices. Man was probably happiest and most stable, Rousseau says, at a level roughly comparable to many precolonial indigenous peoples. Unfortunately for us, the process marches on according to its own internal logic. The invention of metallurgy and agriculture, Rousseau claims, leads to the creation of labor, property, and is the true origin of inequality. Finally, in order for the wealthy property owners to protect themselves from the poor, they create the notion of justice and law and what we would call political society. Once the laws of political society and the political authorities to enforce that law are in place, Rousseau seems to think it is a slow, but inevitable, slide into tyranny, and we come full circle to a new kind of state of nature.

Why This Text is Transformative?

The development of civilization and political society, while bringing great benefits to mankind, is paradoxically the source of most of our evils.

Rousseau with his Second Discourse is a superlative example of the self-critique of the Enlightenment project from within the Enlightenment project itself. The development of civilization and political society, while bringing great benefits to mankind, is paradoxically the source of most of our evils. In fact, the ultimate progress of political society will end in tyranny! This is an innovative text featuring methods and conclusions new to the history of thought. Along with his revolutionary explanation of the origins of inequality in the invention of property, he has equally revolutionary proposals about the origins of language and its development. He engages in the earliest anthropological studies, utilizing physiological and biological arguments, especially in his notes to the text, to make many of his points about the peacefulness of the state of nature.

A Focused Selection

Study Questions

1) Rousseau claims that the different types of government (classically: monarchy, oligarchy, and democracy) arise from the different levels of inequality present at the moment when a political society is created (171). Reflecting on the democracy we live in, it can often seem inefficient and slow to act. Given that monarchies and oligarchies might be more effective and efficient in acting (especially given time sensitive crises like climate change), why might Rousseau say democracies are still preferable? Do you agree?

2) At the end of the Discourse, Rousseau says: “It follows, further, that moral inequality, authorized by positive right alone, is contrary to natural right whenever it is not combined in the same proportion with physical inequality: a distinction which sufficiently determines what one ought to think in this regard of the sort of inequality that reigns among all civilized people; since it is manifestly against the law of nature, in whatever manner it is defined, that a child command an old man, an imbecile lead a wise man, and a handful of men be glutted with superfluities while the starving multitude lack necessities” (180-81, check out the first page of the Discourse to see what he means by moral and physical inequalities). What does Rousseau mean here? When do you think moral inequalities are justified (money, power, honor)? Are there limits to the justification of these inequalities, and if so, what are they?

3) Rousseau gives an argument for why you cannot voluntarily be enslaved and hence why a tyranny can never be legitimate (165-68). Think about what his argument is and how it works. Why would a right to bodily autonomy perhaps permit abortion and prostitution, but not voluntary enslavement?

Building Bridges

A Recommended Pairing

A wonderful short novel by Graham Greene, Monseigneur Quixote, recasts Cervantes’ magnum opus in a way that captures much of the humor and pathos in a more modern context, as the adventures of a Roman Catholic priest and a communist mayor taking to the road together in Spain during the Franco years. The richly imagined characters and their conversations make it clear that the issues that drive Don Quixote’s idealistic quest are not raised only in books of chivalry. How do we live with a commitment to the ideals of a religious faith or a political ideology which, though noble, may not fit easily with and may have unfortunate consequences in the unforgiving world in which we find ourselves? What difference does friendship make in our lives?

Supplemental Resources

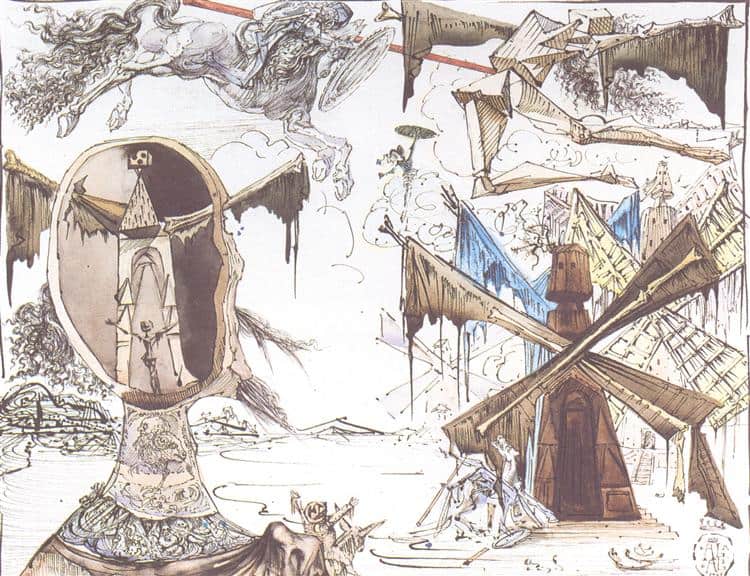

Don Quixote and the Windmills, 1945 - Salvador Dali - WikiArt.org

Don Quixote has been an inspiration for many visual artists. Spanish surrealist Salvador Dali returned to the novel multiple times throughout his long career, creating sketches, paintings, and sculptures of Don Quixote and Sancho, depicting important episodes in the book. A pairing of an episode with one of Dali’s works can lead to a stimulating discussion.

What details do students notice? What do his artistic choices suggest about his interpretation of the characters? To the extent that students are familiar with the story of Don Quixote, it is likely to be as it is filtered through the musical The Man of La Mancha. The musical has its own merits, and is framed by the interesting device of placing Cervantes on stage as a narrator, but of course it is impossible for it to capture much of the complexity of the book – and it alters the ending dramatically. Students may find it interesting to compare the two endings.

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

Political Science/Government

Humanities

Philosophy & Religion

Page Contributor