In this respect, what one can say to those who make assertions about the truth and reality of sensuous objects is that they should be sent back to the most elementary school of wisdom, namely, to the old Eleusinian secrets of Ceres and Bacchus, and that they have yet to learn the secret of the eating of bread and the drinking of wine.

Hegel

Phenomenology of Spirit

Hegel

Terry Pinkard translation. ISBN: 978-0521855792

...Hegel is interested in establishing the highest epistemic regime, which he calls science.

The Phenomenology of Spirit can be seen as a work in epistemology—Hegel is interested in establishing the highest epistemic regime, which he calls science. In order to bring this about, and in order to show how this regime is superior to other systems of knowing, Hegel writes his phenomenology, or his science of the experience of consciousness. Another way of describing the work is that it is the chronicle of the development of “spirit,” variously interpreted as a self-aware social structure and way of life, or, for the more metaphysically inclined, as God. For Hegel, types of knowing are what he calls formations or shapes of consciousness. Dialectic, for Hegel, is the way each formation of consciousness experiences that what it takes itself to be doing or understanding is different from what it is actually doing or understanding—that what it takes its object to be in-itself is merely what it is for that consciousness. This is the “path of despair” in which each formation of consciousness realizes its inherent mismatch between the thing in-itself, or the object, and the way in which that consciousness knows the object, what the object is for consciousness. Of course, often this is only seen from the perspective of the narrator-consciousness that is doing the phenomenological inquiry. In this way, each formation of consciousness inevitably leads to the next, in a series of “determinate negations,” forming what Hegel describes as kind of “self-consuming skepticism,” as the insights of previous formations are taken up and preserved in the next in a process he refers to as “sublimation.” This process leads from the immediate knowledge of objects in the sense-certainty of consciousness, to the dance of establishing normative authority in the master-slave dialectic of self-consciousness, to the full development of spirit, as the product of our collective social structures and cultural practices, and finally to art and religion, as the means by which spirit comprehends and conceives of itself in a culmination Hegel calls “absolute knowing.”

Any sections of the "Phenomenology of Spirit" can be productively read. They will all be difficult but contain flashes of deep insight. Here are some suggestions.

Preface

Introduction

Consciousness: Sensuous-Certainty; or the “This” and Meaning Something

In “Sensuous-Certainty; or the ‘This’ and Meaning Something,” Hegel starts with the consciousness that claims that what is truly known and is certain is the immediacy of what is present in sensation. As this consciousness explores and experiences its claims, it reveals that what it says is not what is meant. Indexicals like, “this,” “here,” and “now,” which are the resources we have for capturing the immediacy of sensuous experience, are themselves quite universal, and rather than picking out the immediate sense-certainties they were supposed to, pick out anything depending on the context of utterance. Furthermore, even if we were to try to lock the referent down by pointing, what was supposed to be the singular this-here-now ends up being composed of an infinite plurality of this-here-now’s. This section serves as an excellent example of the inner contradictions that the dialectic uncovers throughout the text.

Self-Consciousness: The Truth of Self-Certainty

Self-Consciousness: Self-Sufficiency and Non-Self-Sufficiency of Self-Consciousness; Mastery and Servitude

Self-Consciousness has emerged as a new kind of knowing out of Consciousness. Consciousness was focused on knowing as the grasping of an independent object outside of consciousness. Here in Self-Consciousness, the kind of knowing has turned inward to the ways in which consciousnesses contribute to knowing. It is the implicit emergence of spirit. After self-consciousness emerges from life, we have the dialectic of self-consciousness coming to its truth in its recognition by another self-consciousness. Ultimately this will be the mutual recognition of each self-consciousness by the other. At first, each self-consciousness demands from the other recognition of its own value. This takes the form of a life and death struggle, where each tries to establish that it is truly what has value by showing that life means nothing to it, and that it is the self-positing freedom of being-for-itself independent of life. At some point, one self-consciousness emerges that sees life as essential to it—the servant—and another emerges as pure self-positing freedom—the master. The master gets recognition from the servant because the servant works on and processes life to produce things to be consumed by the master. However, the master soon realizes that the truth of his situation is that he is dependent on the servant for the satisfaction of his desires and for the recognition he needs. The servant, in his turn, comes to realize himself as pure self-positing freedom in his work, specifically in the negation that he imposes on life by shaping it and forming it, a negation he was originally unable to perform on life in the original life and death struggle.

Spirit

(Any of the chapters in section VI can be covered. Hegel has insightful analyses of Ancient Greek cultural life that also doubles as an analysis of Sophocles’ Antigone, the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, and Romanticism, among others.)

In this section, this formation of consciousness has emerged as Spirit, which is Hegel’s term for our historically contingent social structures and norms that govern individual beliefs and actions. As Hegel says, it is ethical substance: “Spirit is the ethical life of a people to the extent that it is the immediate truth; it is the individual who is a world.” As the sublation of all the previous formations, Spirit contains them and is the implicit truth of them. Furthermore, the different formations of Spirit are instantiated historically and can be analyzed by studying history: “these shapes distinguish themselves from the preceding as a result of which they are real spirits, genuine actualities, and, instead of being shapes only of consciousness, they are shapes of a world.”

Why This Text is Transformative?

Whatever one may ultimately think of Hegel, reading through the Phenomenology is a philosophical experience like none other, full of “moments” of deep insight as one explores with hallucinatory fluidity his processional-thought terrain.

The Phenomenology of Spirit is arguably one of the most difficult philosophical texts to engage with. Partly this stems from Hegel having to, like Plato and Kant before him, invent terms and phrases to describe ideas and concepts for which ordinary language is inadequate. Because of this, there is not always agreement on just what Hegel is doing. Wherever one comes down interpretively, his impact on the history of thought is undeniable. He is the culmination of German idealism, a philosophical movement that starts with Kant and runs through Fichte and Schelling. His treatment of sense certainty has been taken up by many 20th century critiques of empiricism within the analytic tradition, while the master-slave dialectic has proven to be equally influential within 20th century continental philosophy. Of course, the influence Hegel had on Marx’s dialectical materialism, and hence the historical development of Western radical politics, cannot be overstated. Whatever one may ultimately think of Hegel, reading through the Phenomenology is a philosophical experience like none other, full of “moments” of deep insight as one explores with hallucinatory fluidity his processional-thought terrain.

A Focused Selection

Study Questions

1) How does the immediacy of sense-certainty reveal itself to be a universal? How have concepts or presuppositions you’ve held caused you to misperceive? Can you articulate some aspect of sensation that is not conceptually laden and mediated? Why or why not? What is the role of language here?

2) In the formation of consciousness that is perceptual knowing, how does its object vacillate between a unified thing and a collection of universals? Are things more than a collection of properties? Are you more than a collection of properties? On what grounds are you making this judgment?

3) Paragraph 171 contains Hegel’s analysis of the phenomenon of life. There Hegel says, “The latter, the process of life, is just as much a taking shape as it is the sublating of the shape, and the former, the taking shape, is just as much a sublating as it is a division into groupings.” Do a close reading of this paragraph and explain what he means by this sentence.

4) A system of norms does not arise ex nihilo, but is rather maintained by agents taking those norms as authoritative over them—conceiving them as rules that are not in question for them—and thus acting in light of those norms. How does the master-slave dialectic reveal what Hegel thinks of how normative authority is constituted? What does recognition have to do with this and how is it achieved? What is the role of fear in the authority of norms, and how does one find oneself in the work done according to those norms?

5) In paragraph 177, Hegel describes Self-Consciousness as the implicit emergence of Spirit. He calls it, “The I that is we and the we that is I.” In what way is this an apt description of our social structures and cultural practices? Name some ways in which your contingent social practices have created the I that is you. In what way is it possible for you to authentically participate in those social practices? Are the norms you live by society’s or yours?

Building Bridges

A Recommended Pairing

A wonderful short novel by Graham Greene, Monseigneur Quixote, recasts Cervantes’ magnum opus in a way that captures much of the humor and pathos in a more modern context, as the adventures of a Roman Catholic priest and a communist mayor taking to the road together in Spain during the Franco years. The richly imagined characters and their conversations make it clear that the issues that drive Don Quixote’s idealistic quest are not raised only in books of chivalry. How do we live with a commitment to the ideals of a religious faith or a political ideology which, though noble, may not fit easily with and may have unfortunate consequences in the unforgiving world in which we find ourselves? What difference does friendship make in our lives?

Supplemental Resources

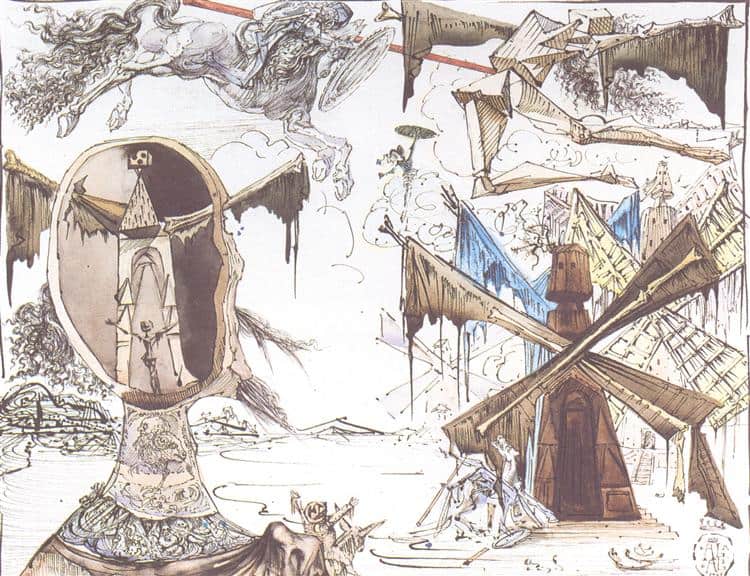

Don Quixote and the Windmills, 1945 - Salvador Dali - WikiArt.org

Don Quixote has been an inspiration for many visual artists. Spanish surrealist Salvador Dali returned to the novel multiple times throughout his long career, creating sketches, paintings, and sculptures of Don Quixote and Sancho, depicting important episodes in the book. A pairing of an episode with one of Dali’s works can lead to a stimulating discussion.

What details do students notice? What do his artistic choices suggest about his interpretation of the characters? To the extent that students are familiar with the story of Don Quixote, it is likely to be as it is filtered through the musical The Man of La Mancha. The musical has its own merits, and is framed by the interesting device of placing Cervantes on stage as a narrator, but of course it is impossible for it to capture much of the complexity of the book – and it alters the ending dramatically. Students may find it interesting to compare the two endings.

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

Sociology

Humanities

Philosophy & Religion

Page Contributor