Here, happy creature, fair angelic Eve,

Partake thou also; happy though thou art,

Happier thou may’st be, worthier canst not be:

Taste this, and be henceforth among the gods

Thyself a goddess, not to earth confined,

But sometimes in the air, as we, sometimes

Ascend to heav’n, by merit thine, and see

What life the gods live there, and such live thou.

John Milton

Paradise Lost

John Milton

Paradise Lost. John Milton. 9780393617085 (Norton Critical Edition) or 9780140424393 (Penguin Classics)

Full free text from Project Gutenberg

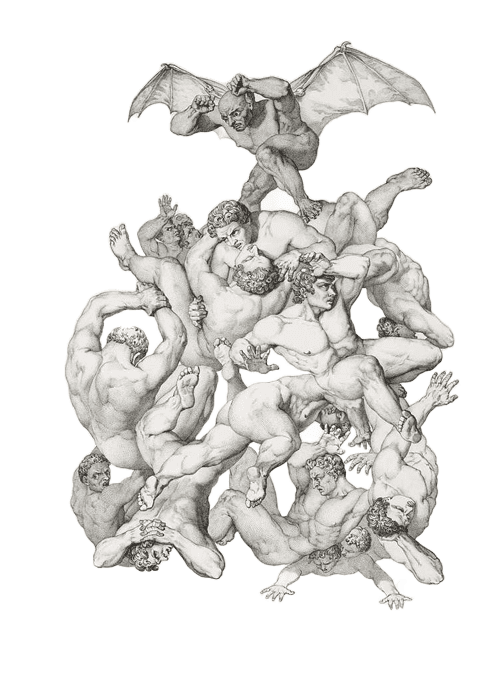

Paradise Lost is John Milton’s retelling of the Fall of Man as Biblical Epic.

In twelve books, Milton narrates Satan’s expulsion from Heaven and decision to corrupt Adam and Eve, God’s creation of Adam and his helpmate Eve, Satan’s visitation to Eden and temptation of Eve and her seduction of Adam, and Adam and Eve’s ultimate removal from Eden. Within this basic narrative, Milton explores God’s decision to allow the Fall to occur, even though he has foreseen it; recounts the war between Heaven and Hell; reveals Satan’s jealousy of Man; and displays Adam’s deliberate decision to follow Eve into estrangement from God. The poem ends ambivalently. Adam and Eve are alienated from God, but they also possess knowledge, free will, and the company of one another.

Why This Text is Transformative?

Paradise Lost poses one significant question after another: Are our paths predestined or do we have free will? Is knowledge good or dangerous? To what lengths will we go for companionship and what is going too far?

Paradise Lost poses one significant question after another: Are our paths predestined or do we have free will? Is knowledge good or dangerous? To what lengths will we go for companionship and what is going too far? What is a righteous ruler and what is tyranny? Is rebellion against tyranny ever permissible or justifiable? What is Hell and what is Paradise? How does a victor emerge in a war between immortals? These are questions without answers, but ones that matter to students and that they relish the opportunity to struggle through. (Actually, Milton makes it pretty clear that a war between immortals will always end in a draw.)

A Focused Selection

If the questions themselves are not hook enough for students, Milton’s most complicated character, Satan, will be. Readers are either seduced by his charm and eloquence or feel sympathy for his experience as an oppressed subject (or child). If Adam is God’s fair-haired creation, Satan is the black sheep, the underdog. Either way, the identification with Satan will disturb readers. This dissonance is productive both in what it can lead readers to understand about themselves and about the nature of art. Did Milton set out to create such a sympathetic creature in Satan? Can an artist’s own creation take on a life of its own? And, in looking at the historical context (specifically, the influence of Milton’s Satan on the English Romantic writers), what are the consequences of creating art that changes the way that human beings understand themselves and their place in the world?

While students might initially balk at the form (Epic Poetry), the length of Paradise Lost, and it’s sometimes challenging syntax, familiarity with the subject matter, Milton’s use of blank verse and an almost notoriously limited vocabulary, and the relevance of the questions raised tends to win them over quickly. The poem renders enough content for days of discussion (not to mention the possibility of days of contextualization), but a lot could be accomplished in two class meetings.

Study Questions

Meeting One: Books I & II

These books cover the fallen angels’ expulsion from Heaven and the meeting of the council of Hell about how to best retaliate against God. Explained are the complaints of these devils against God and the reasons for targeting man as a way to combat God’s perceived tyranny. Questions for Books I and II:

1) Consider the events in Books I and II, as well as what these books tell us about how the fallen angels have been exiled. Given this information, do you consider Satan to be a good leader? Why or why not? What do you consider to be the necessary qualities of a good leader? Have you ever followed a good leader yourself? What about a poor leader? How do you know the difference? How are those experiences different from one another? How does this inform (or how would you like it to inform) your own leadership style?

2) In Satan’s war council, several different voices are heard. Satan opens (lines 11-42), then Moloch (43-108); Belial (108-225); Mammon (229-83); Beelzebub (310-416); and Satan again (416-467). What are the different viewpoints of each of these speakers and why does Satan ask for their input? Which of the perspectives do you find more rhetorically persuasive? Which may represent a kind of action you are more likely to engage in times of struggle? In what situations is it better to appease those in power? Oppose them openly? Move away in order to find peace?

Meeting Two: Books IX & X

Book IX narrates Satan’s temptation of Eve and Adam’s decision to follow her actions and then shows the damage these acts do to their relationship with each other and with Paradise. In Book X, the Son of God is dispatched to judge Adam and Eve, while Satan returns to Hell in triumph and then realizes the consequences of his actions for all Hell’s inhabitants.

1) Paying special attention to Book IX, lines 990-1016, what is the explanation Milton provides as to why Adam eats from the Tree of Knowledge? Think back to choices in your past that you regret or now do not think were good choices, particularly ones in which you have had enough information to make a better decision. What were the pressures or influences that contributed to making those choices? What consequences (good or bad) came from those decisions? Has the way you make choices changed because of those consequences? In what ways?

2) Reading both Books IX and X, what do you make of the relationship between Adam and Eve? What aspects of their relationship—either their romantic relationship or their companionship (after all, they are lovers, friends, and co-workers)—do you deem positive? Which aspects appear to be negative? (And what you see as positive or negative could be the same as Milton seems to judge it or could be different.) What are the qualities that you seek in companions, romantic partners, and co-workers? Are there qualities you want in all three? Qualities you only care about in one of those categories? What do you consider to be our responsibilities to those we are in relationship with?

3) One consequence of the Fall is mortality. In Book X, starting at line 720, Adam begins to struggle with the idea of death and his own mortality. What is your attitude toward death? What does it mean to be mortal, and to live a life knowing that death is its end and consequence? What philosophies or beliefs inform your understanding of death and/or act as your comfort in the face of mortality?

Building Bridges

There are obvious comparisons between Paradise Lost and the Bible, so these texts can be easily read together. Equally, because Milton is attempting to write a Biblical Epic poem, rather than a national or ethnic one, it can be read against any other Epic on the Transformative Text list. But since the text is also about power and leadership, it intersects with texts like The Republic, The Prince, Fear and Trembling, and The Analects. With a focus on Books IX and X, much of which is about the relationship and tension between the sexes (including the idea of division of labor) and about sex and the human condition, these Books can be read in conjunction with The Vindication of the Rights of Woman, The Story of an African Farm, Pride and Prejudice, Mama Day, and The Color Purple. One might argue that reading Paradise Lost is a requirement before reading Frankenstein, considering its influence on the thinking of Mary Shelley and the Romantics generally. The question, it appears, is less “what could Paradise Lost be read in conversation with?” and more “is there any text that Paradise Lost cannot be read alongside?”

Supplemental Resources

The article “Why You Should Re-Read Paradise Lost” from the BBC is a terrific starting point for students, as it gives a short overview of the poem’s context and it’s cultural impact.

Another similar article is “Return to Paradise: The Enduring Relevance of John Milton” from the New Yorker.

Approaches to Teaching Milton’s Paradise Lost is in its second edition and is available directly from the MLA. Additionally, Paradise Lost has inspired many academic papers exploring how to introduce it to undergrads.

A few database searches will turn up scores of articles from various perspectives. See also R.G. Seimens’s “Milton’s Works and Life: Select Studies and Resources.”

For additional texts and context Dartmouth’s The John Milton Reading Room is hugely helpful.

The British Library has resources for teaching Paradise Lost, as well as teaching its context (including visual items).

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

English/Composition Studies

Humanities

Political Science/Government

Page Contributor