When you’re cold, don’t expect sympathy from someone who is warm.

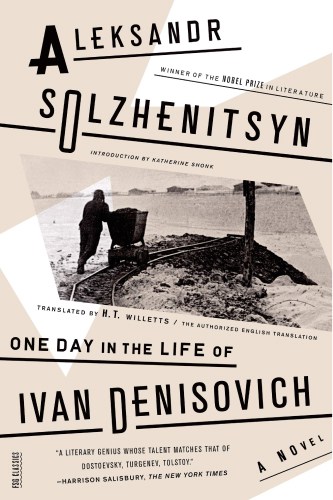

Alexander Solzhenitsyn

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

Alexander Solzhenitsyn

F.H.T. Willetts translation, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 1991 (ISBN 978-0374534684)

There are a number of different translations available. However only the F.H.T. Willetts translation, is based on the full and uncensored text and authorized by the Solzhenitsyn estate. The language is this version is also less stilted than in other translations. The paperback is available on Amazon for under $10.00, so it isn’t a hardship to students to purchase this far-superior version.

This short book doesn’t have a plot in the usual sense. It is simply a description of one day in the life of a prisoner in the Soviet Gulag.

The prisoner is not a prominent prisoner, and perhaps not even exceptional man, and the day is not an exceptional day. If anything, it is a day a little better than many other days. Solzhenitsyn doesn’t portray the extremes of abuse that the prisoners endure in the punishment cells, for example, but rather gives us in painstaking detail the minutiae of everyday life. The horizons of hope and expectation is narrow; Ivan’s mind dwells on the possibility of an extra moment in the bunk, an additional hunk of bread, the relief of avoiding punishment, on small alliances and enmities, and always, always, on the cold.

Why This Text is Transformative?

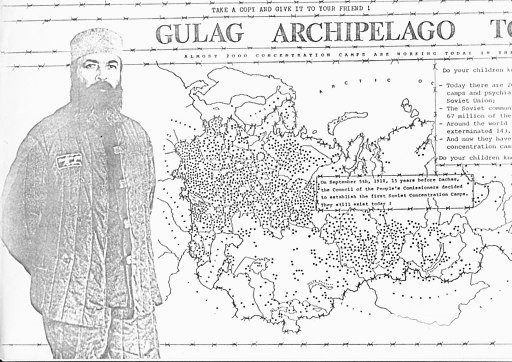

This book was transformational upon publication because of the way in which it exposed the harsh reality of the lives of even unexceptional political prisoners in the huge system of camps that made up the Soviet Gulag.

This book was transformational upon publication because of the way in which it exposed the harsh reality of the lives of even unexceptional political prisoners in the huge system of camps that made up the Soviet Gulag. Along with Solzhenitsyn’s other writings and the works of other artists coming out of the Soviet Union, it contributed to the eventual demise of that system. This can be a good place to start, but for most students the truly transformative aspect of the work will be the questions it raises rather than the abuses it uncovers. What are the limits of our endurance of physical hardship? What do we mean when we say certain sorts of conditions are “dehumanizing?”, and how/or can one’s humanity be maintained through such extreme conditions? What gives a life meaning and purpose day-to-day? What is happiness?

A Focused Selection

It’s difficult to choose a single episode from One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. This is by design. Students will notice that the book doesn’t have chapters or other traditional breaks in the narrative or point of view. It is written to give the impression of a single day that starts in the first sentence with reveille at 5 a.m. and ends when Ivan Denisovich (called by his surname, Shukhov, throughout the book) curls up under the tattered blanket of his bunk in a freezing barrack at night. Given this, it probably makes sense to focus on the end of the work, perhaps beginning at the point where there is a second check of the barracks before lights out. After the tension and turmoil provoked by the search, the inmates settle down again. Strikingly, the book ends on a positive note. Shukhov thinks over the details of his day and ends with the thought that “Nothing had spoiled the day and it had been almost happy.” This is followed by the two final sentences (are these part of Shukhov’s reflection, or the inbreaking of a narrator’s voice?): “There were three thousand six hundred and fifty-three days like this in his sentence, from reveille to lights out. The three extra ones were because of the leap years…”

Study Questions

1) What does it mean that Shukhov can look back on his day and deem it “almost happy?” What is happiness and how is it possible in a situation of such intense physical suffering? Have you ever found yourself unexpectedly happy in an adverse situation? What is that happiness like? Is it different from the happiness that you might feel in a more conventionally “happy” situation? How are you affected by the books ending on the thought of happiness? Is it uplifting, or depressing, or something else?

2) Over the course of Shukhov’s day, the reader encounters several of the other men who work in the camp, especially those of his work-gang. Some are doing relatively well in the camp, and others are going down quickly. Some have the respect of Shukhov and the rest of the prisoners, others are held in contempt. What qualities serve people well, generally, in such extreme situations? Are virtues such as empathy and generosity applicable in a prison-camp? What about intellectual curiosity, or an appreciation for beauty? Is friendship possible, or only alliance based on mutual need?

3) We often refer to such camps and the systems that give rise to them as “de-humanizing” What does the use of this term imply about our assumptions concerning what it is to be human? Is the value and purpose of a human life variable? Do people require a certain degree of physical well-being or certain types of societal organization in order to be fully human? Are some political arrangements inherently inimical to genuine human flourishing?

Building Bridges

A Recommended Pairing

Connections can be drawn between this book and almost any work that depicts humans surviving in situations of extreme physical and psychological degradation, as well as books depicting life in totalitarian political systems.

Supplemental Resources

There is a well-regarded 1970 film directed by Caspar Wrede, with the same title as the book.

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

English/Composition Studies

History

Political Science

Page Contributor