In short, our gentleman became so caught up in reading that…with too little sleep and too much reading his brains dried up, causing him to lose his mind.

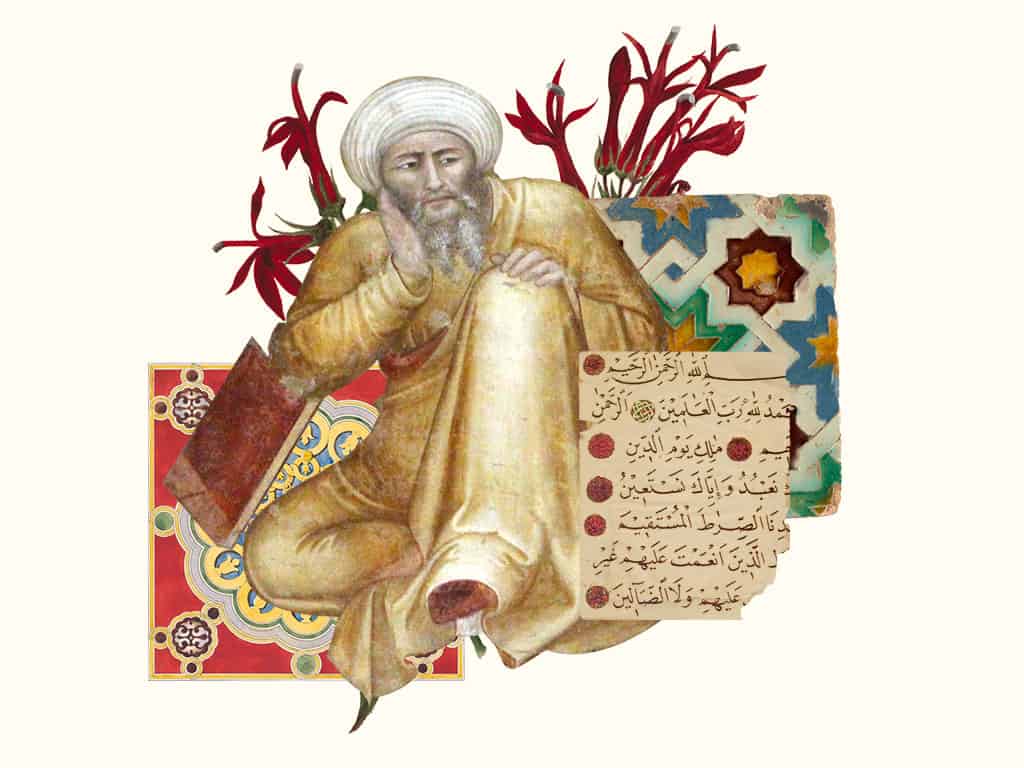

Ibn Rushd (Averroes)

On the Harmony of Religion & Philosophy

Ibn Rushd (Averroes)

Hourani, ISBN: 978-0718902223

...Ibn Rushd also addresses and resolves three main doctrinal conflicts between the Greek philosophical tradition and the Quran: the eternity of the world, God’s lack of knowledge of particulars, and the denial of bodily resurrection.

Chapter 1 of Ibn Rushd’s On the Harmony of Religion and Philosophy is devoted to arguing that not only is studying philosophy permissible according to the Quran, but that the latter makes the study of the former obligatory, but only for those qualified to study philosophy in the first place. As this chapter also makes apparent, philosophical study is not permitted to all equally. It is reserved for those with the right natural talent and moral development, in addition to being lucky enough to have found the proper teacher to guide them in their studies. Chapter 2 argues that when there is apparent conflict between scripture and philosophy, scripture must be interpreted allegorically. Furthermore, there is no real danger of falling into heresy or non-belief in this process, because it is impossible to be certain about what the consensus among Islamic scholars is, due to the fact that these scholars have always held secret, esoteric views, not shared with the public. In this chapter, Ibn Rushd also addresses and resolves three main doctrinal conflicts between the Greek philosophical tradition and the Quran: the eternity of the world, God’s lack of knowledge of particulars, and the denial of bodily resurrection. Finally, chapter 3 is mainly devoted to arguing that these allegorical interpretations are not to be shared with the general (non-philosophically trained) public due to their inability to fully comprehend them. Their general promulgation, Ibn Rushd says, leads the common people to unbelief and causes factions and discord within Islam. In fact, if there is any doubt in the ability of someone to grasp the allegorical meaning of a passage of scripture, the philosopher should lie and deny that there is a deeper meaning entirely!

Why This Text is Transformative?

What is even more radical than Ibn Rushd’s hermeneutic prescriptions, particularly for us, is his insistence that not everyone is capable of the truth, and thus that the truth should not be revealed to everyone equally...

Philosophy, by its very nature of bringing things into question, is at odds with the authority of the political and the religious. So it is no small task that the twelfth century Andalusian philosopher, Ibn Rushd, sets for himself in On the Harmony of Religion and Philosophy. This harmony is achieved by adjusting the Quran to fit Aristotelian philosophical thought through the allegorical interpretation of intransigent passages. That scripture should be interpreted symbolically when it conflicts with demonstrative truths was quite radical for its time, and makes this work important for the history of hermeneutics in general and scriptural interpretation in particular. This work is essential reading for anyone interested in the concept of esoteric and exoteric readings of texts. What is even more radical than Ibn Rushd’s hermeneutic prescriptions, particularly for us, is his insistence that not everyone is capable of the truth, and thus that the truth should not be revealed to everyone equally—for some it can actually be harmful to their ability to believe religious claims and ultimately to their motivation to act morally. Thus this text tangentially brings up questions about the connection between religion and morality.

A Focused Selection

Study Questions

1) What is Ibn Rushd’s solution to the conflict between philosophy’s claim that the world is eternal and scripture’s claim that the world is created ex nihilo? Does it work?

2) What is Ibn Rushd’s solution to the conflict between philosophy’s claim that God has no knowledge of particulars and scripture’s claim of God’s omniscience? Does it work?

3) What is Ibn Rushd’s solution to the conflict between philosophy’s denial of bodily resurrection and scripture’s claim that the body will be resurrected? Does it work?

4) Why does Ibn Rushd believe that not everyone should be told the allegorical meaning of scripture? Do you think that there are some truths that shouldn’t be shared with everyone? Why or why not? What might some examples of such truths be?

Building Bridges

A Recommended Pairing

A wonderful short novel by Graham Greene, Monseigneur Quixote, recasts Cervantes’ magnum opus in a way that captures much of the humor and pathos in a more modern context, as the adventures of a Roman Catholic priest and a communist mayor taking to the road together in Spain during the Franco years. The richly imagined characters and their conversations make it clear that the issues that drive Don Quixote’s idealistic quest are not raised only in books of chivalry. How do we live with a commitment to the ideals of a religious faith or a political ideology which, though noble, may not fit easily with and may have unfortunate consequences in the unforgiving world in which we find ourselves? What difference does friendship make in our lives?

Supplemental Resources

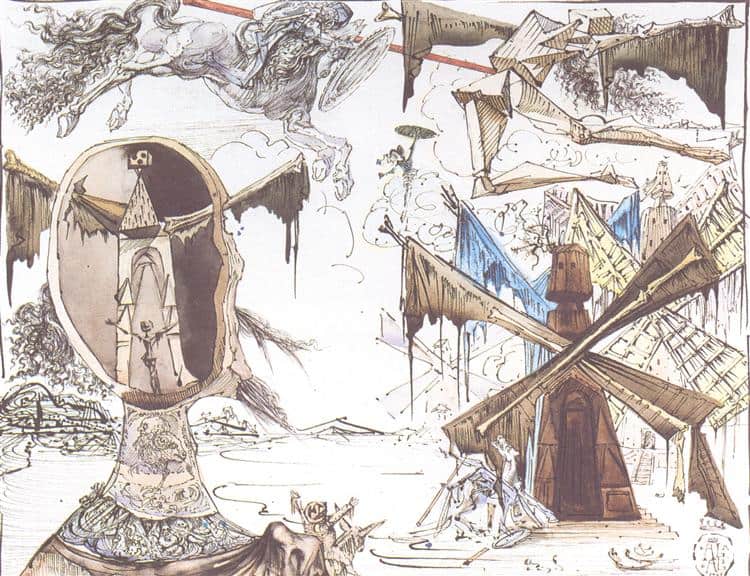

Don Quixote and the Windmills, 1945 - Salvador Dali - WikiArt.org

Don Quixote has been an inspiration for many visual artists. Spanish surrealist Salvador Dali returned to the novel multiple times throughout his long career, creating sketches, paintings, and sculptures of Don Quixote and Sancho, depicting important episodes in the book. A pairing of an episode with one of Dali’s works can lead to a stimulating discussion.

What details do students notice? What do his artistic choices suggest about his interpretation of the characters? To the extent that students are familiar with the story of Don Quixote, it is likely to be as it is filtered through the musical The Man of La Mancha. The musical has its own merits, and is framed by the interesting device of placing Cervantes on stage as a narrator, but of course it is impossible for it to capture much of the complexity of the book – and it alters the ending dramatically. Students may find it interesting to compare the two endings.

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

Sociology

Humanities

Philosophy & Religion

Page Contributor