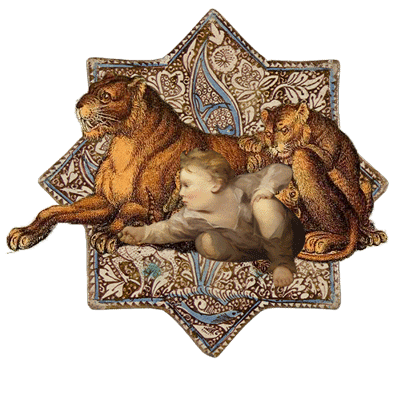

Go ahead and call me lioness…. I do not mind, since now I’ve fairly clawed into your heart.

Euripides

Medea

Euripides

Oliver Taplin translation, University of Chicago Press, 2015. ISBN: 9780226203454. Another good translation is the new Loeb translation, by David Kovac. The Loeb is probably expensive for students to purchase, but a free online version of this translation is available here:

Medea is the harrowing story of a woman who has been betrayed by her husband, Jason, who has abandoned her to marry the young daughter of the King of Corinth.

As the play unfolds she enacts a truly fearsome vengeance, killing not only her husband’s new wife and the Corinthian King, but also her own two children. The play does not end with Medea’s own death, however; rather, she exits the scene exulting in her triumph over Jason, taking the bodies of her sons with her in a chariot provided by her grandfather the sun-god Helios, to bury them at the mountain-top shrine of Hera. Although not one of Euripides more popular plays when it was first produced in ancient Athens, Medea is now regarded as one of the greatest Greek tragedies. It is performed frequently on stage, has been made into movies, and continues to resonate in contemporary culture.

Why This Text is Transformative?

It is helpful in the classroom that that the beautiful but challenging poetic language and the stylized, unfamiliar character of ancient Greek drama provide enough distance for students to be able to be able to examine the most violent emotions and actions, creating the opportunity for compelling discussion.

This is a short, riveting text that takes students directly to topics about human nature in extremity – questions of passion, the relationship between love and hatred, justice and the most severe vengeance extending even to children. It is almost impossible not to react strongly. It is helpful in the classroom that that the beautiful but challenging poetic language and the stylized, unfamiliar character of ancient Greek drama provide enough distance for students to be able to be able to examine the most violent emotions and actions, creating the opportunity for compelling discussion.

In addition to the questions that are clearly raised by the story itself, the play also raises very explicitly other issues that resonate strongly with students. Medea is a proud, fierce female who speaks eloquently of the lot of women: “We women are the most beset by trials/of any species that has breath and power of thought,” and of captives: “Manhandled from a foreign land like so much pirate loot.” Her actions are horrifying, but – the text makes clear – so are the crimes that have been committed against her. Jason, defending himself against her accusations, speaks as the representative of the colonial power, explaining to Medea the benefits he has conferred upon her by taking her from her home and “civilizing” her: “… you inhabit Greece/ instead of some barbarian land;/ you’ve gotten to experience the rule of justice and the law.”

A Focused Selection

This text is already very focused: the Taplin translation for example is only 60 pages long, and the story unfolds at a breathless pace from the opening speech of the nurse to the appearance of Medea with the bodies of her children in the chariot of the sun. The final section of the play, beginning with Medea’s final resolution to kill her children at around line 1235 and ending with her disappearance with their bodies, can be a good place to get discussion started. Once the trajectory of Medea’s actions becomes clear, students are likely to expect that the play will end with Medea’s death as well, either at the hands of Jason and the Corinthian people or by suicide. But, as the chorus chants in the final lines, “The endings expected do not come to pass.” Instead, Medea is displayed to us as physically elevated, exulting in her undiminished rage and her triumph over Jason, with plans to bury her sons and establish a religious cult in their honor.

Study Questions

1) At the end of this play, Medea’s fury is unabated. Her last words in the play are in response to Jason’s request to touch the bodies of the children: “Unthinkable. Your words are wasted in air.” What is it like to be consumed with rage? Euripides’ ending puts an emphasis on Medea’s lineage as the granddaughter of Helios; she is separated from human beings in a chariot provided by the gods. How does great anger separate us from others? Is there anything about it that is elevating, as well as terrifying? What might bring such rage to an end? Is it sometimes appropriate that anger be unending?

2) Early in the play, the chorus of Corinthian women has professed friendship and sympathy toward Medea, and even agreed to remain quiet about her plans for revenge. As it become clear that these plans involve killing her children, however, they begin to protest, first to Medea, then to Helios, that he should save his descendants. At line 1275 they resolve to enter the house and save the boys themselves – but do nothing. What is it that keeps them from interfering in Medea’s actions? Fear? Some element of sympathy for her that still remains? A sense that justice is being served? A feeling of helplessness? Have you been in a situation of standing by while something dreadful takes place? What is it that makes action hard in such circumstances?

3) Is the appearance of Medea in the chariot a vindication of her actions? Or can you think of another interpretation? What might make a person capable of taking the action she did, and are such actions ever justifiable? Medea claims both that she kills the boys to torture Jason, and that she kills them because otherwise they will fall into the hands of those who will make them suffer more horribly. Is one or the other a truer explanation of her actions?

Building Bridges

In order to connect the story of Medea to a context closer to home, pair it with Toni Morrison’s Beloved. Morrison’s classic novel is based on the story of a woman slave named Margaret Garner who escapes to Ohio and who, like Sethe, kills one of her children and tries to kill the others to avoid having them taken back into slavery. Garner was dubbed by contemporaries “The Modern Medea.” The theme of infanticide is an obvious commonality, along with questions about how individuals and entire societies are shaped by past trauma, what it means to be free, and whether murder can be an act of love. Inviting students to compare their reactions to the two invites an examination of the possibility and extent of empathy.

Supplemental Resources

There are many excellent versions of Medea available for viewing online. Most are films of stage productions. Medea, a 1969 film by Pier Paolo Pasolini, is an effective and relatively faithful take on Euripides’ story, though it leaves out much of Euripides’ language.

The 1978 Greek film directed by Jules Dassin, A Dream of Passion, tells the story of an actress playing Medea who seeks out a woman in prison who has murdered her children to punish her husband for infidelity.

Especially interesting in making the connection to Beloved is material about Margaret Garner, such as this page from the collection of the New York Public Library:

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

English/Composition Studies

Humanities

Political Science/Government

Page Contributor