You shouldn’t be at war! …..We’re going to save you, whether you like it or not!

Lysistrata

Lysistrata is an extremely bawdy comedy about the attempts of the women of Greece to bring an end to a long, bloody war.

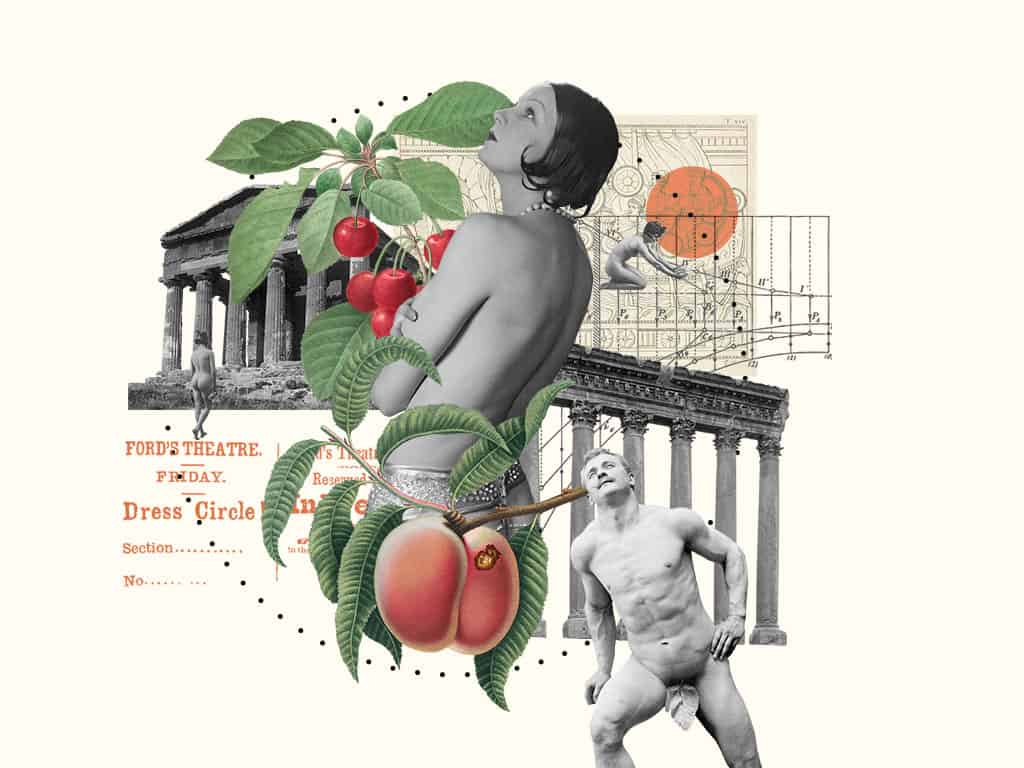

Lysistrata, an Athenian woman, supported by Lampito, a leader among the women of the enemy Spartans, bring together the women of the country to swear that they will not have sex with any man until the men have ended a decades-long war. As a supportive strategy, a group of the older women have taken over the treasury at the Acropolis where the civic wealth of Athens is stored, so that the men can’t access money to refit their warships. The majority of the play consists of exchanges between the women and the men. The chorus of older men confronts the chorus of older women in an unsuccessful attempt to enter the treasury. Younger men returning from battle are teased by their wives to inflame their desire, but then refused sexual gratification. An Athenian magistrate has a conversation with Lysistrata about how the women think the state should be governed. There is a brief rebellion among the women, who themselves also desire sex, but Lysistrata convinces them to hold to their resolution. The Athenian men become increasingly desperate, and when an equally frustrated delegation arrives from Sparta they are presented with Reconciliation – in the form of a beautiful naked woman. The two sides quickly negotiate a peace and the play ends with singing and dancing.

Why This Text is Transformative?

This text raises very directly questions about the role of women in society, about the place of war, and about the role of sexual desire both in individual relationships and in relation to the state.

This text raises very directly questions about the role of women in society, about the place of war, and about the role of sexual desire both in individual relationships and in relation to the state. Students are likely to sympathize strongly with the Lysistrata, who is far more than simply the leader of the sex strike. In her attempts to persuade the women to forgo sex (which, the play makes very clear, they enjoy as much as the men) and in her conversations with the magistrate, she reveals herself to be a talented leader and someone who has given serious thought to the proper administration of the state. We feel her fury when she answers the magistrate’s question “What have you [women] ever done for the war effort?” by cursing him and pointing out that they have contributed the most essential thing of all – their sons, who have gone to war and not returned. Unlike much Ancient Greek drama, the play is not violent or particularly disturbing, except in the extremely explicit nature of the humor (the men walk around with huge erections for most of the play). This is likely to be surprising to many students, who may have the idea that older works are necessarily staid. Students and faculty alike may struggle with finding language they are comfortable using in class discussion. This discomfort, if not pushed too far, is itself interesting. Why is this embarrassing? Why is sexual humor funny – in Ancient Greece and still today?

A Focused Selection

Study Questions

1) Aristophanes makes it clear that the women of Athens and Sparta enjoy sex as much as the men. Their oath to abstain involves a list of the various acts and unusual positions that they will miss (for example “the lioness and the cheese-grater!”). It is evident that the boycott is successful not because the women love sex less than do the men, but because they hate war so much more. Why is that the case? Is there something that the men value in the activity of war? If so, what might that be? Are there times when war is the better alternative? In Greek society and in our own, war often provides the arena for certain acts of virtue and heroism. Should a society seek to cultivate and control martial impulses, or to eradicate them?

2) The dialogue between Lysistrata and the magistrate makes it clear that women and men occupy very different places in Athenian society. Men take charge in the public arena, in areas of finance, commerce, international affairs. To women are delegated the tasks associated with running households and personal estates, bearing and raising children, and taking care of tasks such as cooking and weaving that support everyday life. The men can, and do, tell their wives not to express opinions in areas outside the private sphere – a stance surely called into question by Aristophanes’ depiction of the play’s remarkable heroine. In addition to throwing this division of roles into question, however, Lysistrata’s analogy of the wool makes the case that women would run the city better than men specifically because they are skilled in the tasks of running a household. Do you think that this is right? What sort of preparation do you think makes a person more or less prepared to build and lead a community? What sort of values are embodied in the community woven in the image offered by Lysistrata?

3) What does our ability to be controlled by the manipulation of sexual desire say about our what it is to be human? What place does or should the erotic play in our lives? Do you find the depiction of sexuality in Aristophanes funny? Is it very different than the way sex might be depicted in a raunchy comedy today? What is the effect of bringing something usually private to the center of public discourse?

Building Bridges

A Recommended Pairing

Interesting connections can be drawn between Lysistrata and almost any text that

Supplemental Resources

Medea, a 1969 film by Pier Paolo Pasolini, is an effective and relatively faithful take on Euripides’ story, though it leaves out much of Euripides’ language.

There are many excellent versions of Medea available for viewing online. Most are films of stage productions. Medea, a 1969 film by Pier Paolo Pasolini, is an effective and relatively faithful take on Euripides’ story, though it leaves out much of Euripides’ language. The 1978 Greek film directed by Jules Dassin, A Dream of Passion, tells the story of an actress playing Medea who seeks out a woman in prison who has murdered her children to punish her husband for infidelity. Especially interesting in making the connection to Beloved is material about Margaret Garner, such as this page from the collection of the New York Public Library:

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

English/Composition Studies

Humanities

Area Studies

Page Contributor