I put for a general inclination of all mankind, a perpetual and restless desire of power after power, that ceaseth only in death.

Thomas Hobbes

Leviathan

Thomas Hobbes

Hobbes, Thomas, and E. M. Curley. Leviathan : with selected variants from the Latin edition of 1668. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co, 1994. Print. ISBN 978-0-87220-177-4

Also Online for free. This edition updates the language and may be easier for students to read, though some interpretive liberties were taken in this updated edition.

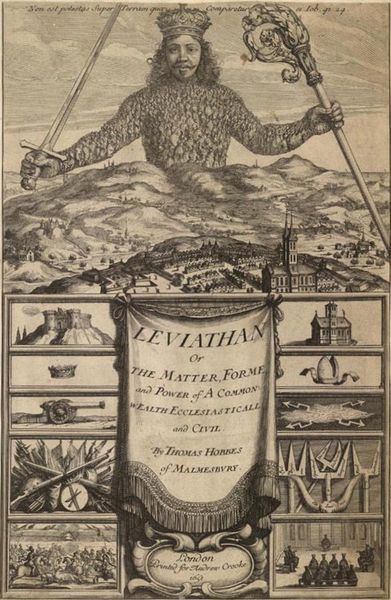

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), published Leviathan in 1651 during the English Civil War.

Moved by the horrors and instabilities of this conflict as well as by the previous religious wars over issues of doctrine, Hobbes sought to find a more stable foundation for politics. In this seminal text he claims to deduce fundamental truths about human moral and social interaction, which lead him to conclude that stable and strong governments are best based upon a social contract between individuals for the sake of the mutual protection of their liberties and their physical security.

Why This Text is Transformative?

This text is a classic of political philosophy and foundational for social contract theory, which in part influenced the framing of the US Constitution and other modern political forms.

Hobbes’ text is one of the most transformative texts in this history of political thought. This text is a classic of political philosophy and foundational for social contract theory, which in part influenced the framing of the US Constitution and other modern political forms. While pre-hobbesian politics was concerned with the moral and spiritual development of citizens, the modern political projects ushered in by authors like Hobbes were decidedly not. Hobbes was a pioneer in applying the modern scientific method to the study of politics. He saw his work as bringing light into the “kingdom of darkness”, which is how he characterized the understanding of human moral and social life before the application of the scientific method to their study. Hobbes was to the study of politics what Francis Bacon was to the study of nature; truly revolutionary. The political thought of Hobbes continues to influence us today in our taste for representative political institutions, our deference to the will of the majority and in our understanding of the pursuit of power as fundamental to all human action.

A Focused Selection

A challenge in reading Hobbes with students is his style of writing, which may present itself to many students as dry and rather boring. Another difficulty is that many of his radical conclusions may appear obvious and therefore not worth thinking about for the number of students who held them to be true before reading them in Leviathan. The key to overcoming this difficulty is to press students on the points where they agree with Hobbes and ask them to articulate his arguments for them and to emphasize that Hobbes was one of the first people to articulate some of these ideas that they came to class believing were true. Are they? How strong are Hobbes’ arguments for these positions? Are there better arguments to be made for them? What are the arguments one may advance against them? If students can appreciate the degree to which our thinking about politics and social life is a product of Hobbesian influence, understanding his text becomes more urgent and important. Who is this long dead person who shaped my thinking about important matters? How did he do that and why?

Study Questions

Part 1, Chapter 10, Power, Worth, Dignity, Honour, and Worthiness could make for engaging class discussion and introduction to Hobbes in the consideration of these study questions, which include an interactive small group activity.

1) What is Hobbes’ definition of power? Make a list of the ways in which you are most powerful, according to Hobbes’ understanding of power, and explain the benefit of these powers in Hobbesian terms. For example, if you regard your physical appearance as a power of yours, you may say, in Hobbesian terms, that your appearance is power because it prejudices people to regard your intentions as good.

2) What is the distinction Hobbes makes between Science and arts of public use and what is their relationship to one another? Why is Science less powerful than arts of public use when the latter depends upon the former? Which professionals in our world today practice science and which practice arts of public use, as Hobbes understands these terms? Which of these professionals are esteemed the most and why?

3) Exchange the list of your powers that you made for question 1 with a classmate. Considering Hobbes’ definition of Worth, value each of your classmates’ powers in terms of the price you would pay for the use of them. Who is most honored? Are there other qualities you possess that Hobbes would not consider to be powers but which you believe should be regarded in the evaluation of your individual worth? What are they and why should they be considered in the estimation of your individual worth?

4) Near the beginning of Chapter 11, Hobbes writes, “I put for a general inclination of all mankind, a perpetual and restless desire of power after power, that ceaseth only in death.” Hobbes believes that the quest for power is a part of every human interaction and relationship. In which of your relationships does this seem to be the most true and in which does it seem least true?

Building Bridges

Supplemental Resources

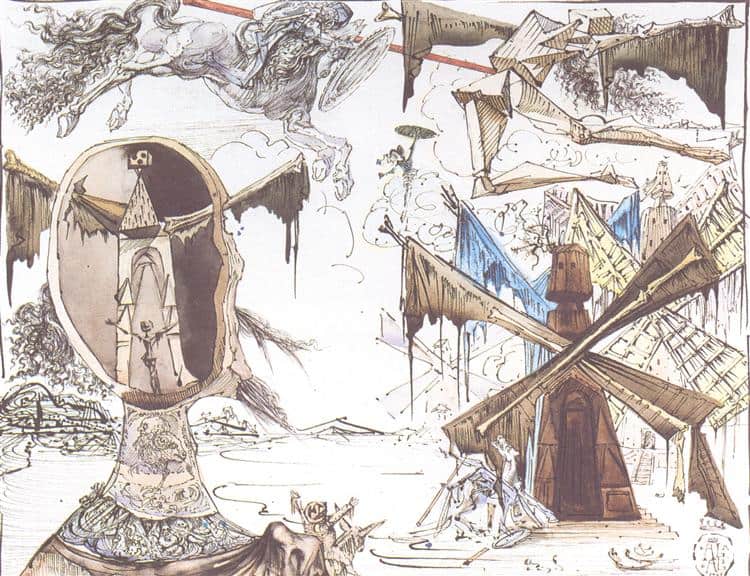

Don Quixote and the Windmills, 1945 - Salvador Dali - WikiArt.org

Don Quixote has been an inspiration for many visual artists. Spanish surrealist Salvador Dali returned to the novel multiple times throughout his long career, creating sketches, paintings, and sculptures of Don Quixote and Sancho, depicting important episodes in the book. A pairing of an episode with one of Dali’s works can lead to a stimulating discussion.

What details do students notice? What do his artistic choices suggest about his interpretation of the characters? To the extent that students are familiar with the story of Don Quixote, it is likely to be as it is filtered through the musical The Man of La Mancha. The musical has its own merits, and is framed by the interesting device of placing Cervantes on stage as a narrator, but of course it is impossible for it to capture much of the complexity of the book – and it alters the ending dramatically. Students may find it interesting to compare the two endings.

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

Political Science/Government

History

Philosophy & Religion

Page Contributor