“I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imaginations—indeed, everything and anything except me” (3).

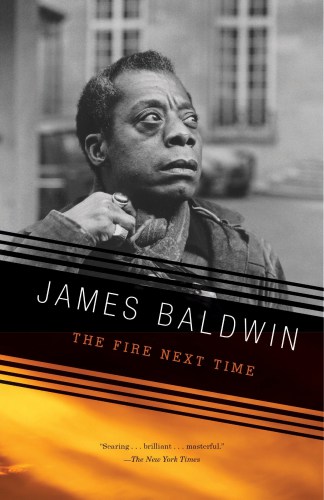

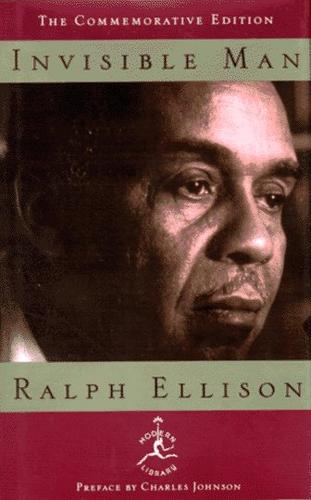

Ralph Ellison

Invisible Man

Ralph Ellison

Ellison, Ralph. Invisible Man. Modern Library, 1994

An unnamed narrator introduces himself as an “invisible man” because people he meets on the street are incapable of “seeing” him.

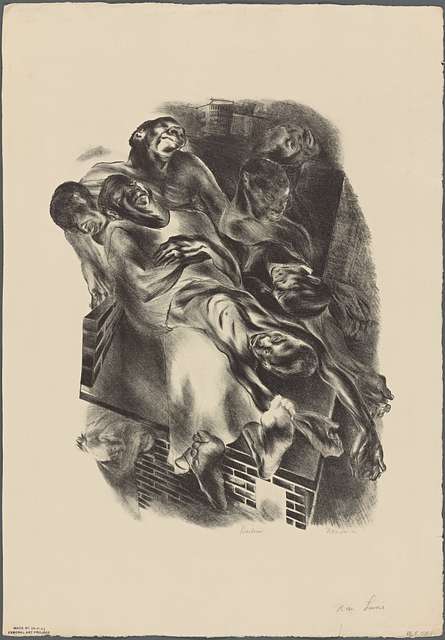

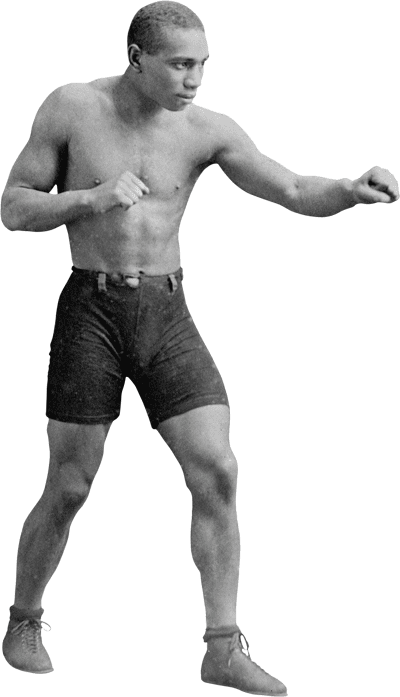

He lives “rent-free” (5) in closed off section of a basement and steals electricity to fill his living space with light, which, he claims, “confirms [his] reality, gives birth to [his] form” (6). He then tells the story of the last twenty years of his life, beginning with a speech he gave at his southern high-school graduation (“in which I showed that humility was the secret, indeed, the very essence of progress” [17]). The speech later earns him, after his forced participation in a brutal, sadistic, and humiliating boxing match for the amusement of civic leaders, a scholarship to “the state college for Negroes” (32). After his expulsion from college, he leads a challenging life in New York’s Harlem among a variety of people, including those of the politically radical Brotherhood, an activist group which holds to communist principles of equality, and Ras the Exhorter (and, later, the Destroyer), “the wild man who calls himself a black nationalist” (357). (“They were laughing [but I knew] that Ras was not funny, or not only funny, but dangerous as well, wrong but justified, crazy yet coldly sane…. Why did they make it seem funny, only funny?” [555].) Although he had attempted to forget his past, he eventually embraces his memories, recognizing that, “I was my experiences and my experiences were me” (500). After narrowly escaping being killed by Ras and his militant followers, the narrator falls into a manhole, and he remains underground, recognizing his reality and realizing his “invisibility.” However, he resolves to accept his status: “[N]ow I denounce and defend, or feel prepared to defend. […] I denounce because though implicated and partially responsible, I have been hurt to the point of abysmal pain, hurt to the point of invisibility. And I defend because in spite of all I find that I love” (570). In the end, he pledges to soon emerge from his underground home, to “shake off the old skin” (571) because “there’s a possibility that even an invisible man has a socially responsible role to play” (572). Although the narrator doesn’t know what is to come, he has reached a better understanding of himself and the world.

Why This Text is Transformative?

The book provides countless opportunities for reflection on Black (and White) identity, politics, class, race, and Black bodies (including “visibility” and “invisibility”).

Ellison’s Invisible Man is one of the great American novels of the last 100 years. It combines an impressionistic portrait of a nameless protagonist and his journey as part of the Great Migration of Black Americans to the north during the early part of the twentieth century. Published in 1952, the work speaks to a pivotal moment in history, as many aspects of American society were scrambled and reinvented in the years following World War II. The book also traces the tumultuous events of the civil rights movement, including the various and often opposing social factions within the Black community and the frequent acts of civil disobedience and riots (including the Harlem Riot of 1943 that inspired the closing scenes of the novel). The book provides countless opportunities for reflection on Black (and White) identity, politics, class, race, and Black bodies (including “visibility” and “invisibility”). The Candide-like innocence of the protagonist in much of the novel provides many opportunities for both horror and humor, as he is pushed this way and that by ideology and political expediency. In the seventy years since its publication, the variety of responses the novel has produced speaks to a universal appeal that seems to shift with social and political winds. The work has provoked much thought-provoking commentary and criticism, highlighting “the text’s ability to fit simultaneously into and challenge any number of theoretical grids, from the American novel since World War II to the African American novel, from problems of canon formation to questions about minority and postcolonial discourse” (“Ralph Ellison” 246). As a result, students often find that the experiences of reading and reflecting on the novel reveal a great deal about their own lives.

A Focused Selection

Like the Prologue, the Epilogue, parts of which are excerpted here, synthesizes the narrator’s insights regarding his experiences. Like Chapter One (“Battle Royal”), these framing sections of the novel are often studied independently and provide commentary on the novel as a whole.

“Yes, but what is the next phase? How often have I tried to find it! Over and over again I’ve gone up above to seek it out. For, like almost everyone else in our country, I started out with my share of optimism. I believed in hard work and progress and action, but now, after first being “for” society and then “against” it, I assign myself no rank or any limit, and such an attitude is very much against the trend of the times. But my world has become one of infinite possibilities. What a phrase—still it’s a good phrase and a good view of life, and a man shouldn’t accept any other; that much I’ve learned underground. Until some gang succeeds in putting the world in a strait jacket, its definition is possibility. Step outside the narrow borders of what men call reality and you step into chaos—ask Rinehart, he’s a master of it—or imagination. That too I’ve learned in the cellar, and not by deadening my sense of perception; I’m invisible, not blind.

“No indeed, the world is just as concrete, ornery, vile and sublimely wonderful as before, only now I better understand my relation to it and it to me. I’ve come a long way from those days when, full of illusion, I lived a public life and attempted to function under the assumption that the world was solid and all the relationships therein. Now I know men are different and that all life is divided and that only in division is there true health. Hence again I have stayed in my hole, because up above there’s an increasing passion to make men conform to a pattern. Just as in my nightmare, Jack and the boys are waiting with their knives, looking for the slightest excuse to . . . well, to “ball the jack,” and I do not refer to the old dance step, although what they’re doing is making the old eagle rock dangerously.

“Whence all this passion toward conformity anyway?—diversity is the word. Let man keep his many parts and you’ll have no tyrant states. Why, if they follow this conformity business they’ll end up by forcing me, an invisible man, to become white, which is not a color but the lack of one. Must I strive toward colorlessness? But seriously, and without snobbery, think of what the world would lose if that should happen. America is woven of many strands; I would recognize them and let it so remain. It’s “winner take nothing” that is the great truth of our country or of any country. Life is to be lived, not controlled; and humanity is won by continuing to play in face of certain defeat. Our fate is to become one, and yet many—This is not prophecy, but description. Thus one of the greatest jokes in the world is the spectacle of the whites busy escaping blackness and becoming blacker every day, and the blacks striving toward whiteness, becoming quite dull and gray. None of us seems to know who he is or where he’s going” (566-68).

Study Questions

1) How would you explain the paradox that “our fate is to become one, and yet many” (568)? How is this statement, as Ellison writes, “description” rather than a “prophecy”? Is such a fate possible? What would a state of being “one, yet many” look like?

2) What does “invisibility” mean in The Invisible Man? Give examples of how Ellison depicts “invisibility” in the story. Do you ever feel that you are “invisible” in your day-to-day life? Do you choose this state of invisibility, or it is imposed on you by society?

3) In Chapter One (“Battle Royal,” pp. 15-33), what does the battle royal represent? That is, for what might it be a metaphor? In what ways do you face “battles royal” in today’s society? Who must face them most often, and why?

4) Throughout the novel, why is it significant that the protagonist repeatedly is chosen to represent his race and yet he remains nameless?

5) What does the narrator in Invisible Man desire in life? Throughout and by the end of the work, does he believe there is something that will give him a place in the world in which he is living? If so, what is it? If not, why not? Do you feel that there is a place in the world for you? How might your personal situation compare and contrast with that of the narrator of the novel?

Building Bridges

Although the writings of Ta Nehisi Coates are often compared with those of James Baldwin, examining Coates’s Between the World and Me also can highlight some of the persistent themes addressed in Ellison’s Invisible Man. The concept of Black bodies, as signifiers of identity, as shorthand for racist ideology, and as targets of social and political violence, is in many ways the basis for both works. Ellison’s protagonist pursues “invisibility” as a means of survival, but this invisibility is a state that the narrator comes to understand in the novel: it is a result of White society’s indifference to his individual identity and contempt for his “Blackness.” This indifference and contempt are seen throughout the book. For example, the novel begins with objectification of Blackness that obviates the identity of those who inhabit those bodies. Chapter One’s “Battle Royal” is filled with racist comments from the White civic leaders, who in their excitement and drunkenness repeatedly call for harm to come to the Black bodies in the make-shift boxing ring (21 ff.). As another example, the narrator witnesses police shoot and kill an unarmed member of the Brotherhood, Tod Clifton, (and the narrator subsequently gives a heart-felt, extemporaneous eulogy at his funeral that, sadly, still resonates today [447-52]). Afterward, the narrator must defend his perception of why Clifton was killed to the members of the Brotherhood, who insist that he was killed because of his ideology and his being a representative of their group. The narrator states, “[Here in Harlem] we know that the policemen didn’t care about Clifton’s ideas. He was shot because he was black and because he resisted. Mainly because he was black. […] And as for the dolls [Clifton had been selling on the street], they know that as far as the cops were concerned Clifton could have been selling song sheets, Bibles, matzos. If he’d been white, he’d be alive. Or if he’d accepted being pushed around…” (460-61).

In much the same ways, Coates’s Between the World and Me, in the form of a letter to his fifteen-year-old son, is both an appreciation of and a warning about Black bodies, about the violence that awaits his “visible” son in his own day-to-day life. Early in the work, after Coates lists several Blacks recently killed by police, he states, “And you know now, if you did not before, that the police departments of your country have been endowed with the authority to destroy your body. It does not matter if the destruction is the result of an unfortunate overreaction. It doesn’t matter if it originates in a misunderstanding. It does not matter if the destruction springs from a foolish policy. […] The destroyers will rarely be held accountable. Mostly they will receive pensions. And destruction is merely the superlative form of a dominion whose prerogatives include frisking, detainings, beatings, and humiliations. All of this is common to black people. And all of this is old for black people. No one is held responsible” (9). Later in the work, Coates explains how the Black body must be controlled in order to survive: “But you are a black boy, and you must be responsible for your body in a way that other boys cannot know. Indeed, you must be responsible for the worst actions of other black bodies, which, somehow, will always be assigned to you. And you must be responsible for the bodies of the powerful—the policeman who cracks you with a nightstick will quickly find his excuse in your furtive movements” (71). Coates’s work complements Ellison’s novel in ways that reveal the perennial and universal challenges experienced by Black Americans, both historically and in today’s world.

Supplemental Resources

Oklahoma Historical Society, Film Interview with Ellison (28 min.)

Documentary on Ralph Ellison (1:26:00 min.)

Art Institute of Chicago: Invisible Man: Gordon Parks and Ralph Ellison (2 min.)

Art Institute of Chicago: Gordon Parks, Off on My Own (Harlem, New York) Collaborations with Ellison (7 min.)

Jarenski, Shelly. “Invisibility embraced: the abject as a site of agency in Ellison’s Invisible Man.”

MELUS, vol. 35, no. 4, winter 2010, pp. 85+. Gale Literature Resource Center, (Invisibility and Black male subjectivity and power)

Messmer, David. “Trumpets, Horns, and Typewriters: A Call and Response between Ralph

Ellison and Frederick Douglass.” African American Review, vol. 43, no. 4, winter 2009, pp. 589+. Gale Literature Resource Center (Black language and culture as seen through rhetorical experience in the novel.)

“‘The Next Time You Got Questions Like That, Ask Yourself’.” African American Review, vol.

51, no. 4, winter 2018, pp. 273+. Gale Literature Resource Center Accessed 6 Jan. 2022. (On “Blackness”)

Parr, Susan Resneck, and Pancho Savery, eds. Approaches to Teaching Ellison’s Invisible Man. MLA, 1989.

“Ralph Ellison.” Headnote. The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, 3rd ed., vol. 2, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and Valerie Smith, eds, Norton, 2014, pp.243-47.

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

English/Composition Studies

History

Sociology

Page Contributor