And now Lord take my life: I should be better dead than alive. ‘Are you so angry?’ said the Lord?

-Book of Jonah, Chapter 4

Hebrew Bible & New Testament

There are too many translations of the Hebrew Bible and of the New Testament to enumerate here, many of them excellent. It probably makes sense to steer students away from familiar but archaic versions like the King James and the Douay-Rheims-Challoner in favor of something more contemporary like the New International Version, New English Bible, or the New Living Translation or, for the Hebrew Bible, the Jewish Publication Society’s JPS Tanakh. Quotations on this page are taken from the New English Bible.

It is an important founding document of several religious traditions, made up of a variety of different writings, and different types of writings, with many authors.

The Hebrew Bible (also known as the Tanack or the Old Testament) is, as its various names reveal, a contested text. It is an important founding document of several religious traditions, made up of a variety of different writings, and different types of writings, with many authors. Fundamentally it presents the story of the relationship of a people to their God, but this story is interpreted differently by the different groups for whom this book is part of the sacred narrative. Centering these interpretations and their associated truth claims in the classroom makes reading this text together extremely difficult. On the other hand, the text opens up and can becomes the occasion for fruitful exploration when a class focuses on a single story or poem within the whole. The New Testament, also the work of a variety of authors, is the primary sacred text of Christianity, and also positions itself as an interpretation of the Jewish scriptures.

Why This Text is Transformative?

These texts have shaped entire civilizations and innumerable individual lives, and most students will be aware that much is at stake in discussing them.

The transformational power of the Hebrew Bible and New Testament is undeniable. Both make claims about the human relationship to the divine, the origins and nature of the world, and the sort of life one ought to live in response to these truths. These texts have shaped entire civilizations and innumerable individual lives, and most students will be aware that much is at stake in discussing them. The challenge in class is make possible a serious engagement that respects the stances taken by a wide variety of students – from those who live within the faith traditions these texts represent, to those who are more or less indifferent to religious truth claims, to those who actively reject them.

A Focused Selection

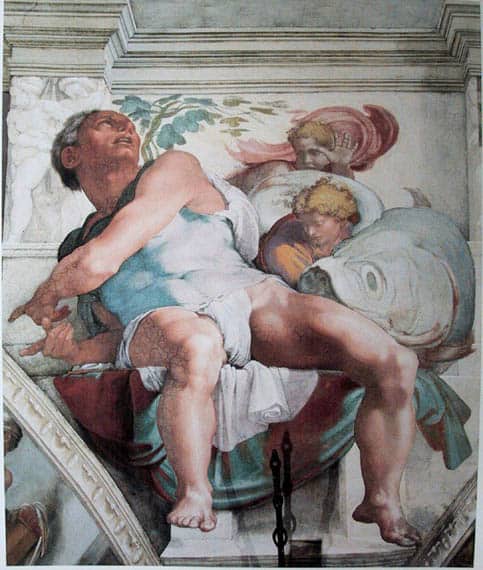

This page will focus on the book of Jonah, a short, coherent story one episode of which (Jonah’s being swallowed by a whale or large fish) will probably be familiar to many students. The story begins when Jonah is tasked by God with going to preach to the people of a foreign city, telling them to repent. He attempts to escape God’s election but is unable to do so and eventually (thanks in part to the large fish) finds himself proclaiming the word of God to the city’s people. The tale concludes in chapter four with an unexpected twist. Instead of being gratified, Jonah is surprised – and resentful – when his preaching is successful and leads to widespread repentance, saying to God “And now Lord, take my life: I should be better dead than alive.” The ensuing events and the dialogue between Jonah and God make this a great place to begin a conversation.

Study Questions

Why is Jonah so angry that the people of Nineveh have repented and been spared God’s wrath? He even says that he feared this outcome from the beginning, and it is the reason he tried to escape God’s call. Why would he not welcome such an outcome? Have you ever been angry at your own success, or disappointed by an outcome that seems positive?

Jonah’s story begins with his attempt to travel to a place “out of reach of the Lord.” What does it mean to try to escape from God? Are there fates or vocations in our lives that we cannot avoid? In the case of Jonah even the forces of nature (the sea and the big fish) seem to collude to force him to complete the task God has assigned to him. Can such a vocation coexist with any sense of freedom?

As part of the dialogue in chapter four, God gives and then takes away a plant that provided shade while Jonah observed the people of Nineveh whom he has helped save from destruction. What is this purpose of this? After the plant withers, Jonah again says that he would be better off dead, and in response to questioning by God says that he is “mortally angry.” God juxtaposes Jonah’s anger at the death of the plant with his anger at the survival of the people of Nineveh and their cattle. What does this show to Jonah, and what might it reveal to the reader?

Building Bridges

The story of Jonah pairs well with that of another man seeking unsuccessfully to evade a calling from God. St. Augustine’s Confessions tells the story of his struggle avoid giving himself over to the Christian faith. Like Jonah he travels across the sea, in this case from his birthplace near Carthage in northern Africa to Italy. Unlike Jonah he arrives at his destination and even achieves enormous success in his life there – but is unable to find peace, and experiments with several belief systems before finally, in a crisis, coming back to the faith in which he was raised. How do his motivations for fleeing the call compare to those of Jonah? Both men accede with reluctance, but their reactions after they have resigned themselves to following God’s insistent demand are very different – Jonah is angry, while Augustine find peace and relief. How might we account for this difference?

Supplemental Resources

The story of Jonah is important in the Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions. A short slide-show of classic art from all three traditions, taking Jonah as its subject, is available from Wikipedia:

The figure of Jonah remains current in American culture – showing up for example in music from traditional gospel: Oh Jonah | Library of Congress

To pular song: Paul Simon| Jonah

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

English/Composition Studies

Humanities

Philosophy & Religion

Page Contributor