The tavern keeper said to him, to Gilgamesh:

Gilgamesh, wherefore do you wander?

The eternal life you are seeking you shall not find.

When the gods created mankind,

They established death for mankind,

And withheld eternal life for themselves.

As for you, Gilgamesh, let your stomach be full,

Always be happy, night and day.

Make every day a delight,

Night and day play and dance.

Your clothes should be clean,

Your head should be washed,

You should bathe in water,

Look proudly on the little one holding your hand,

Let you mate be always blissful in your loins,

This, then, is the work of mankind.

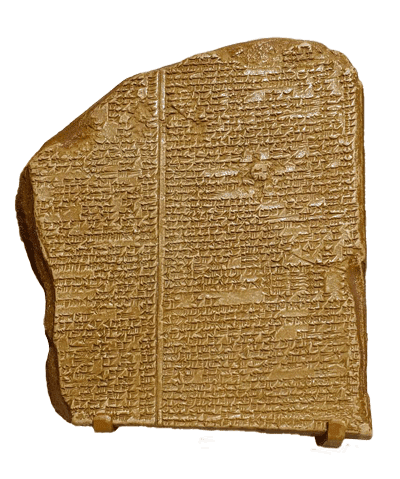

From Tablet X, ll. 37-82

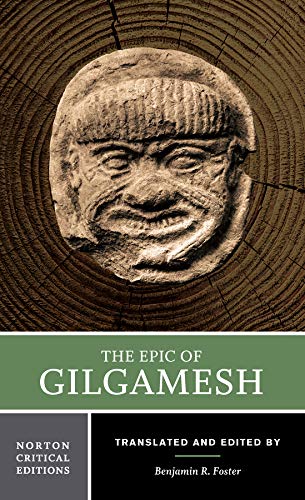

The Epic of Gilgamesh

Foster, Benjamin R., ed. and trans. The Epic of Gilgamesh. Norton Critical Editions, Norton, 2019

When Gilgamesh, the powerful, brave, and beautiful leader of Uruk, is first seen, he behaves as an arrogant tyrant, abusing his authority with men and women.

As a result, the people cry out to the gods, who in response create Enkidu, a wild man with shaggy hair all over his body who lives as a beast with other animals. After hearing reports of Enkidu’s existence, Gilgamesh sends Shamhat, a temple prostitute, to seduce Enkidu. After six days and seven nights with Shamhat, the beasts no longer allow Enkidu near them; his time with Shamhat humanizes and civilizes him, and “he had gained reason and expanded his understanding” (1.194). Enkidu is as physically powerful as Gilgamesh, and initially they fight, but after neither prevails, they become deeply close friends, and they seek out adventures and challenges throughout the world. After one particularly strenuous battle, the goddess Ishtar notices Gilgamesh bathing and tries to seduce him. Gilgamesh makes the mistake of insulting Ishtar, leading her to seek revenge by sending the Bull of Heaven to punish the two men. After they defeat the bull, the gods decide one of the men must die. Gilgamesh refuses to accept Enkidu’s death until a maggot crawls out of Enkidu’s nose. Gilgamesh is profoundly frightened by his sudden awareness of his own mortality, and in seeking ways to achieve eternal life, he travels to meet Utanapishtim and his wife, who survived the Great Flood and were granted eternal life. In the end, Gilgamesh returns to Uruk, perhaps with the greater understanding that although each individual human life will end, the human race will prevail and carry on our memory. He praises the great walls of Uruk, which will preserve his legacy forever.

Why This Text is Transformative?

The poem is full of exciting adventures, ... but it is also a profound meditation on the meaning of being human...

The Epic of Gilgamesh is one of the oldest pieces of literature, and the character Gilgamesh is the first epic hero. The poem is full of exciting adventures, as the demi-god Gilgamesh (sometimes with Enkidu) defeats monsters and other-worldly creatures, but it is also a profound meditation on the meaning of being human; human achievement and limitations; power and violence; civilization (and its responsibilities) and savagery; travel and homecoming; youth and age; suffering and maturity; knowledge, wisdom and understanding; the fear of death and appeal of eternal life; the duties of a good leader; as well as friendship, fame, culture, sexuality, and love. Although the gods are present in the action, the story less a myth about the actions of the gods or a religious poem than it is about human behavior and the achievement of understanding and wisdom. Story elements first found in Gilgamesh (such as hero arrogance and hubris; hero-friendships; the Underworld; the Great Flood; the revenge of gods on humans; the wandering hero; and angry, vengeful female humans and gods) are commonly found in later epics, including Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, The Hebrew Bible / Old Testament, the Aeneid, and many other works of world literature. Finally, the story conveys a profoundly affecting humanity undiminished in the 4,000 years since it was first composed.

A Focused Selection

Study Questions

Tablet 7

1) Tablet VII includes a recounting of two of Enkidu’s dreams. How do dreams function in the poem? Are they a force of good, what Gilgamesh calls “a most precious omen, though very frightening” (7.30)? Do they guide humans or confuse interpretation? Do these dreams come from the gods, or do they reflect the challenges and anxieties of the characters? Where do you think your dreams come from, and do you think it’s helpful to interpret them to provide guidance for yourself?

2) Enkidu curses the hunter for his part in reporting Enkidu’s existence to Gilgamesh and who “did not let me get as much life as my friend” (7.51). He also curses Shamhat, the prostitute who civilizes him, because she “diminished me, an innocent” (7.85). Is Enkidu’s complaint legitimate? That is, in what way have the hunter and Shamhat “diminished” Enkidu by civilizing him? Consider the benefits of civilization and savagery as described in the poem. How might your own life be improved by more “savagery” and less “civilization”?

3) Shamash, the sun god, admonishes Enkidu for his curses in Tablet 7, helping Enkidu to recognize and appreciate the importance of Shamhat, and later Gilgamesh, in the process of his self-knowledge, comfort, and happiness through being civilized. Other gods and goddesses are incorporated into the action of the poem, either to help or punish the human characters. Do the gods guide the humans toward peace and goodness, or are they as varied and capricious in their motives and actions as the humans? In this context, how does the demi-god Gilgamesh, two-thirds god and one-third human, function in the poem?

4) Consider Gilgamesh’s response to Enkidu’s death in Tablet 8. In what ways is the death of Enkidu in Table 7 the climax of the poem? Trace the journey of both men from savagery to civilization. How does the death of Enkidu ultimately lead to Gilgamesh’s deeper understanding of what it means to be human? Has the death of someone in your life changed you and your way of looking at your own life, as well as the world around you? Do you feel you have a better understanding as a result, or did the pain of loss further confuse your understanding of life?

Building Bridges

The Great Flood narrative in Gilgamesh can be paired with the Great Flood story from Genesis 6-9. As with other flood narratives from around the ancient world, there are many similarities, but the differences are significant, including the relationship between God / the gods and the protagonist. In each case, what is the purpose of the flood? For what are humans being punished? Why is the protagonist (Utanapishtim / Noah) chosen to survive? How does a particular god / God communicate with the protagonist, and for what purpose? (A related point is the overall effect of the polytheistic vs. monotheistic structure of the respective religion on the narrative.) How does the pursuit of knowledge by humans differ in Gilgamesh and Genesis?

Supplemental Resources

Barron, Patrick. “The Separation of Wild Animal Nature and Human Nature in Gilgamesh: Roots of a Contemporary Theme.” Papers on Language and Literature, vol. 38, no. 4, 2002, pp. 377-94

Jager, Bernd. “The Birth of Poetry and the Creation of the Maier, John, ed. Gilgamesh: A Reader. Bolchazy-Carducci, 1997

Jager, Bernd. “The Birth of Poetry and the Creation of the Human World: An Exploration of The Epic of Gilgamesh.” Journal of Phenomenalogical Psychology, vol. 32, no. 2, 2001, pp. 131-54

A future edition the MLA Approaches to Teaching series on The Epic of Gilgamesh

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

English/Composition Studies

History

Area Studies

Political Science/Government

Page Contributor