His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead

–The Dead

James Joyce

Many critics have described the paralysis the characters exhibit and the pervading sense throughout the stories that they are living a life in death.

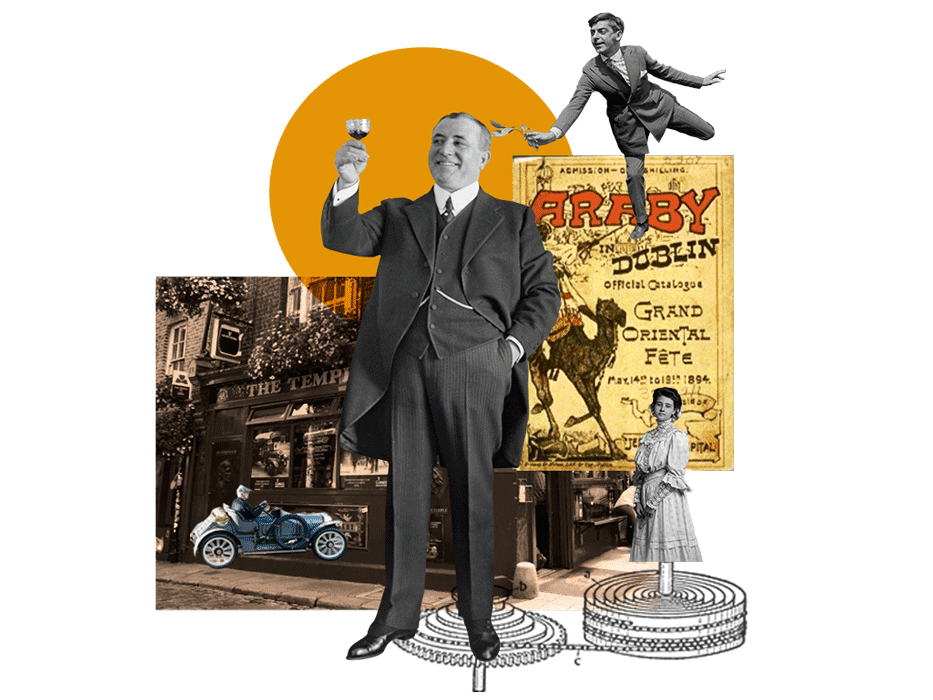

There are fifteen stories collected in Dubliners, linked through a common longing for adventure and exotic locals (often symbolized in images of the east, which includes England and Europe, as well as Asia) set against the paralysis of the characters because of their naivety, their poverty, and their provincialism. Many critics have described the paralysis the characters exhibit and the pervading sense throughout the stories that they are living a life in death. Many of the characters look toward the east for their escape from Dublin, including Jimmy Doyle in “After the Race,” who is “too excited” being in the company of his European companions, who literally and metaphorically take him for a ride; the boy in “Araby,” who has adopted colonial attitudes of mystery and exotic eroticism around the East and imagines the bazaar “cast an eastern enchantment”; and the characters like Gallaher of “A Little Cloud” and Gabriel of “The Dead” who have adopted European manners; Molly Ivers calls Gabriel a “West Briton.” In Dublin, London is symbol of sophistication and progress. As Little Chandler walks toward his meeting with Gallaher, for example, we are told, “Every step brought him nearer to London, farther from his own inartistic life.” Yet in these stories, the east holds a trap: Jimmy Doyle’s significant loss during the card game, the disappointment of the bazaar, its darkness, commercialism and the distinctly English accents the boy hears once he arrives; the stuffed and pompous delusion that Gabriel recognizes in himself at the end of “The Dead.” Alternately, the west becomes a more likely, if more terrifying, route of for movement. Rather than the refinement and decadence of Europe or the mystery and exoticism of Asia, imagining toward the west represents a recognition of Ireland’s roots, represented by characters like Molly Ivers and Michael Furey in “The Dead,” Kathleen Kearny in “A Mother” and Frank in “Eveline.”

Paradoxical to all this movement east and west, the characters of Dubliners are mostly stuck, Gabriel at the end of “The Dead” being the exception as he thinks of setting out on his journey west, which, however, is also the direction of the graveyard. With its the pervasive images of lifeless lives, as well as the collection’s opening image of Father Flynn’s death in “The Sisters” and the final image of Michael Furey’s ghost in “The Dead,” there is also throughout the stories a feeling of being haunted. Michael Furey in “The Dead” and Emily Sinico in “A Painful Case” are ghosts that possibly appear within these stories, but there are other senses of haunting, as Eveline’s mother’s words haunt the daughter’s life and keep her paralyzed within her constrained life, even as Eveline weekly wipes the dust that collects in the house, keeping the dead at bay but never ridding her life of its presence. The dead have an uncanny presence within the stories, existing on parallel planes with these characters who, whether from poverty or provincialism, cannot find a way to escape their paralysis.

Why This Text is Transformative?

These stories can introduce students to the Joycean epiphany, the moment at the end of the stories when a profound truth gets revealed to the characters.

These stories can introduce students to the Joycean epiphany, the moment at the end of the stories when a profound truth gets revealed to the characters. At the end of “A Painful Case,” Mr. Duffy “felt that he was alone.” The boy in “Araby” says, “I saw myself a creature driven and derided by vanity.” The boy’s realization is not so different from Jimmy Doyle’s realization of his “folly” at the end of “After the Race,” Little Chandler’s shame and remorse at the end of “A Little Cloud” as he sees the hatred in his wife’s eyes and understands his ineptitude in the domestic life he has chosen over his art, or even Gabriel Conroy’s in “The Dead” seeing himself as “a ludicrous figure, acting as a pennyboy for his aunts, a nervous wellmeaning sentimentalist, orating to vulgarians and idealizing his own clownish lusts, the pitiable fatuous fellow he had caught a glimpse of in the mirror.” Gabriel, however, follows his epiphany more deeply than other characters in the collection, his shame turning into “generous tears” for Gretta’s lost passion and the realization that “one by one they were all becoming shades. Better to pass boldly into that other world, in the full glory of some passion, than fade and wither dismally with age.” These realizations the characters have about themselves are often the things that we cover with defenses. Conversations about these realizations in the characters can be a way to have students consider the blindnesses in their own lives.

A Focused Selection

Study Questions

The following set of questions are for “Araby”

What are the narrator’s associations with Araby that makes the bizarre draw on his imagination so strongly? Can you think of a space that holds powerful associations for you? What would be an example of a place like that for you? What do you associate with that place that instills it with such emotional power? What might your associations say about your values and dreams?

What does the boy actually find at the bizarre? List some of the things he sees and hears and what associations these things might have for him.

An epiphany is a character’s sudden realization. For Joyce, who created the use of the epiphany, the understanding can feel beyond rational explanation. What is the narrator’s epiphany? Is there anything you can find in the story that helps to understand how he arrived at this epiphany?

The following set of questions are for “The Dead"

What do you notice about Gabriel in his first interactions with his wife, his aunts and Lily? List some characteristics that you see as particularly important.

Describe the interactions between Molly Ivers and Gabriel. Why does he not want to go to Aran Isles? What does that trip represent to Gabriel? If he were to travel, where do you think he would rather go instead?

Gabriel worries about giving his speech. What does he say in his speech? Summarize it in a couple of sentences. Do his thoughts and actions throughout the party give evidence that he believes what he has said? Cite evidence from the text to support your reasoning.

What effect does Gretta’s story have on Gabriel? Follow their interactions from when Gretta says “I am thinking about a person log ago who used to sing that song” until Gretta falls asleep. What emotions does Gabriel go through during this conversation?

What happens in the silence that follows the conversation? What are some of the things that Gabriel realizes about himself? Does this change any responses you had to him earlier in the story? What is his final realization? Many other characters in the collection have similar epiphanies to the one that Gabriel has. How is Gabriel’s epiphany different from some of the others in the collection? Do you think Gabriel will be different after this?

Building Bridges

A Recommended Pairing

Frankenstein

One of the themes that reoccurs throughout these stories is thwarted ambition. It could be interesting to pair Dubliners with narratives of unchecked ambition, such as Frankenstein or Macbeth.

White Teeth

Alternatively, Zadie Smith in White Teeth deals with English identity and colonization, similar to Joyce’s concerns in Dubliners. However Zadie Smith’s attitude is one of humor. Pairing Smith and Joyce for tone and attitude could lead to interesting questions. Smith also brings full characterization to “the east” that so fascinates Joyce’s characters.

Supplemental Resources

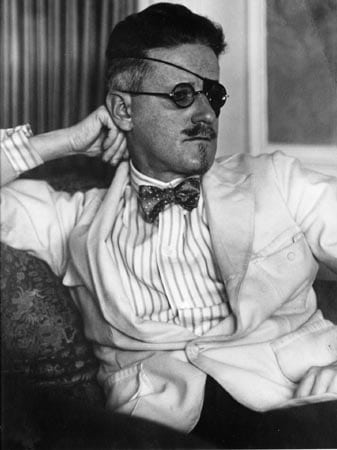

James Joyce & His Glorious Eyepatch

British Library

James Joyce Center

James Joyce Checklist: Bibliography of Joyce Criticism with links

Yale Modernism Lab/James Joyce

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

English/Composition Studies

Humanities

Area Studies

Page Contributor