I became […] a creature eaten up and emptied by fever, languidly weak both in body and mind, and solely occupied by one thought: the horror of my other self (60).

Robert Louis Stevenson

Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde

Robert Louis Stevenson

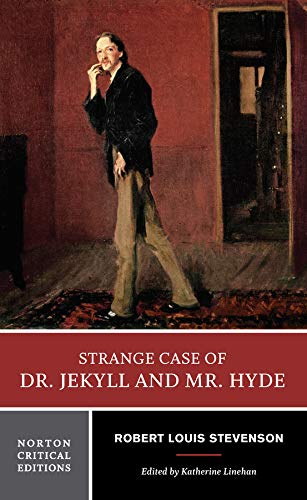

Linehan, Katherine, ed. Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson. Norton Critical Edition, Norton, 2003

While on a walk through London’s Soho neighborhood, Enfield discusses with Utterson an incident he witnessed where a man named Hyde trampled a small girl and left her screaming on the street.

The man is accosted, he agrees to pay the girl’s family for what he has done, and he produces a check written by Dr. Jekyll, whom Utterson knows. He also learns that Jekyll has created a will that leaves everything he owns to Hyde. They both assume that Hyde is blackmailing Jekyll. Utterson visits the building where Hyde had earlier entered for the money of the girl and meets Hyde before going to Jekyll’s house (on the other side of the same building), where Jekyll’s servant, Poole, tells him that Jekyll is not home. Many months later, Hyde is identified as beating an old man, Carew, to death with a cane. After Utterson brings the police to Hyde’s home and not finding him, he confronts Jekyll, who gives him letters from Lanyon (Jekyll’s old friend) and Hyde, letters he is not to open until Jekyll has died. Jekyll seems better, but then begins not seeing people. Sometime later, Poole asks Utterson to the home of Jekyll, whom Poole fears has been murdered by Hyde, However, when they break in, they discover Hyde’s dead body (in Jekyll’s clothes), as well as a will and letter from Jekyll to Utterson. From these documents (and Lanyon’s letter) we learn that Jekyll had created a potion that allowed him to separate himself into two halves, one which would remain socially respectable and the other which would allow him to indulge in his impulses and desires. Although the potion worked at first, soon he began to turn into Hyde without warning and without the aid of the potion. It was in this state that he murdered Carew. Also, he is unable to reproduce the potion. The novel ends with his confession, and we are left to believe that either Jekyll or Hyde commits suicide.

Why This Text is Transformative?

Jekyll is, however, an amazingly rich tale of a human who pursues indulgence in unspecified pleasures, vices, or criminal actions while attempting to maintain social respectability in Victorian society.

Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is suitable for a variety of community college courses and can be included in units of differing lengths and focuses. A seemingly simple story of approx. 60 pp., the novel has been frequently dismissed as “sensationalist fiction” concerned only with lurid, grisly violence and depravity. Jekyll is, however, an amazingly rich tale of a human who pursues indulgence in unspecified pleasures, vices, or criminal actions while attempting to maintain social respectability in Victorian society. As a result, in addition to literature and composition courses, the text is useful as a basis of discussion in the environments of psychology, sociology, criminology, genetics and physiology, human sexuality, gender studies, LGBTQ+ studies, and others. Jekyll can be studied through many lenses: the power and ethical boundaries of scientific exploration; evolution and degeneracy; fate, free will, and human agency; sin and responsibility; repression and the pleasures of the body; hypocrisy; the definitions good and evil and the tension and distinction between these forces; drug and alcohol addiction; madness; dreaming and sleep; heteronormative anxiety and homosexuality; the “double” and split personality vs. the unified “self”; and the study of genre (religious allegory, social expose, fable, detective story, horror thriller, sensational fiction, science fiction, literature of the doppelganger, and Gothic novel [See Norton 124, head note])

A Focused Selection

“Hence it came about that I concealed my pleasures; and that when I reached years of reflection, and began to look round me and take stock of my progress and position in the world, I stood already committed to a profound duplicity of life. Many a man would have even blazoned such irregularities as I was guilty of; but from the high views that I had set before me, I regarded and hid them with an almost morbid sense of shame. It was thus rather the exacting nature of my aspirations than any particular degradation in my faults, that made me what I was and, with even a deeper trench than in the majority of men, severed in me those provinces of good and ill which divide and compound man’s dual nature. In this case, I was driven to reflect deeply and inveterately on that hard law of life, which lies at the root of religion and is one of the most plentiful springs of distress. Though so profound a double-dealer, I was in no sense a hypocrite; both sides of me were in dead earnest; I was no more myself when I laid aside restraint and plunged in shame, than when I laboured, in the eye of day, at the furtherance of knowledge or the relief of sorrow and suffering. And it chanced that the direction of my scientific studies, which led wholly towards the mystic and the transcendental, reacted and shed a strong light on this consciousness of the perennial war among my members. With every day, and from both sides of my intelligence, the moral and the intellectual, I thus drew steadily nearer to that truth, by whose partial discovery I have been doomed to such a dreadful shipwreck: that man is not truly one, but truly two. I say two, because the state of my own knowledge does not pass beyond that point. Others will follow, others will outstrip me on the same lines; and I hazard the guess that man will be ultimately known for a mere polity of multifarious, incongruous and independent denizens. I for my part, from the nature of my life, advanced infallibly in one direction and in one direction only. It was on the moral side, and in my own person, that I learned to recognize the thorough and primitive duality of man; I saw that, of the two natures that contended in the field of my consciousness, even if I could rightly be said to be either, it was only because I was radically both; and from an early date, even before the course of my scientific discoveries had begun to suggest the most naked possibility of such a miracle, I had learned to dwell with pleasure, as a beloved daydream, on the thought of the separation of these elements. If each, I told myself, could but be housed in separate identities, life would be relieved of all that was unbearable; the unjust might go his way, delivered from the aspirations and remorse of his more upright twin; and the just could walk steadfastly and securely on his upward path, doing the good things in which he found his pleasure, and no longer exposed to disgrace and penitence by the hands of this extraneous evil. It was the curse of mankind that these incongruous faggots² were thus bound together – that in the agonized womb of consciousness, these polar twins should be continuously struggling. How, then, were they dissociated?” (48-49).

Study Questions

1) Dr. Jekyll believes “life would be relieved of all that was unbearable” (49) if there were a separation of good and evil within a person. Did the creation of Hyde accomplish this? Was there, in fact, a true separation of good and evil? Explain. Do you think it is possible to separate the “good” and “evil” in yourself? What benefit would there be for you if this separation were possible?

2) As we will also see in Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, the “text turns out always to hover around, never to reveal, the specific pleasures that Jekyll is eager to pursue through the guilt-free anonymity of Hyde” (xii). What sorts of activities do you believe Hyde indulges in? Why these? Support your answer with details from the text.

3) In the novel, Jekyll observes, “all human beings […] are commingled out of good and evil: and Edward Hyde, alone in the ranks of mankind, was pure evil” (51). Why is this so? That is, why couldn’t Hyde be pure good instead? Jekyll sees himself, and presumably all humankind, as a “composite” (55), or half good / half evil; the potion that Jekyll/Hyde drinks, it seems, has no moral force. Why is Hyde all bad? (See pp. 48-49 and 51-52 for some discussion, but expand your answer to include ideas from the book as a whole.)

4) In the last part of the novel, we learn from Dr. Jekyll himself how he came to be divided into both Jekyll and Hyde. Jekyll speaks here of “the infamy at which I thus connived” (53). The Norton edition states that, at the time, according to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), “connive” meant “to shut one’s eyes to an action that one ought to oppose, but which one covertly sympathizes with; to wink at, be secretly privy or accessory” (53, n. 1). How does this older definition of “connive” speak to Jekyll’s character and motives? Look especially at pp. 47-62, and describe how Jekyll is divided among “shutting his eyes,” “opposing” the actions of Hyde, and simultaneously “covertly sympathizing” with Hyde’s behavior.

5) To what degree are fate and free will factors in Jekyll’s transformation into Hyde? That is, would you argue that Jekyll clearly chooses to indulge his darker side or that, once Jekyll, a man of science and learning, discovers the possibility of separating his two natures, that he can only pursue the “experiment” of such a division? Also, to what degree does his own naturally divided human nature influence his decision? To what degree is biology “so determinative of our beings as to preclude the possibility of free will” (99, n. 5)? Do you think fate or free will controls your life? Would separating your “good” from your “evil” help you take better control of your life?

6) How is the novel an indictment of hypocrisy? How does the book demonstrate the darker forces that are inside of all of us, ones which we keep carefully hidden from the view of society? Discuss the novel, and support you answer with details from the text. (See also p. 48, note 4; and pp. 146-49.) Do you ever feel like such a hypocrite? Are there things that you keep “hidden from the view of society”? Is such hiding necessary for you? What sorts of things are important to hide, and why? (See questions #7-#10, below).

7) The novel also can be seen as an allegory about homosexuality in a society in which such desires and behavior must be strictly hidden. How might the book be seen as “‘a signing to the male community’ about Stevenson’s awareness of painful self-divisions fostered in men by Victorian dread of homosexuality” (98, n. 2)? (See also pp. 138-40.)

8) The novel can also be seen as a study of drug and alcohol addition, criminality, and/or the psychology of split personality. Discuss some or all of these possible readings. (See also pp. 132-38.)

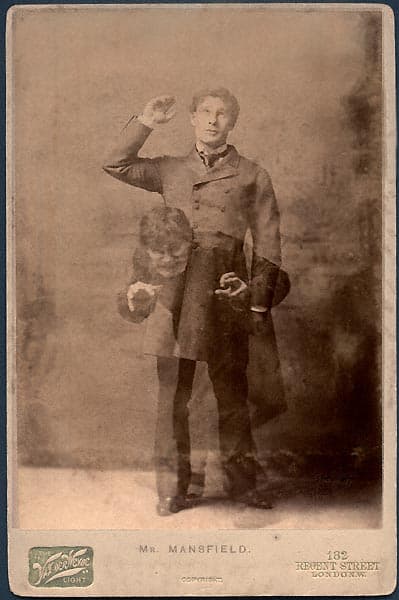

9) Trace the development of the doppelganger in literature and how Stevenson’s novel uses and expands upon those traditions. (See also pp. 124-26.)

10) Although the novel lacks any main female characters and there is little suggestion of outright sexual behavior, how can the novel be seen as revealing the sexually repressed undercurrent of the characters and the larger Victorian society that produced the work? (See also pp. 204-13.)

Building Bridges

A Recommended Pairing

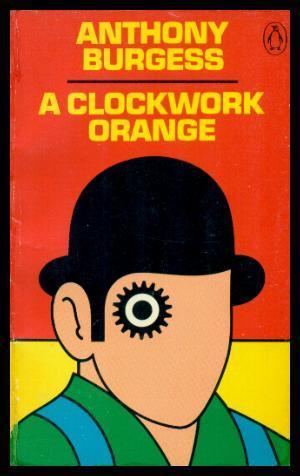

Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde could be profitably paired with Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange (1962). Both works concern constraints on free will and the forces of conscience, social norms, and punishment. The narrative arcs of the two works are in some ways opposite: Dr. Jekyll moves from a position of social respectability to degradation and suicide, while Alex moves from a gleeful embracement of pleasure through several types of violence to a redemption of sorts when he eventually matures out of adolescence. Jekyll believes that “man is not truly one, but truly two” (48), and he learns “to recognize the thorough and primitive duality of man […], that of the two natures that contended in the field of my consciousness, even if I could rightly be said to be either, it was only because I was radically both” (49). In this way, A Clockwork Orange is both opposite that similar to Jekyll: Alex’s ability to act is circumvented through “science,” a Pavlovian “Ludovico Technique” which deprives him of his free will. However, ultimately Alex chooses to desist in his destructive behavior through natural maturation vs. the unnatural “clockwork orange” treatment which renders Alex a person who appears natural on the outside (“an orange”) but who is actually deprived of his natural ability to choose (“clockwork”). Jekyll, in contrast, uses “science” to similarly control his actions by neatly separating his two natures into different iterations of self. However, similar to Alex under the influence of the “Lodovico Treatment,” he loses control of his free will, transforming without warning or the assistance of “science” into an increasingly violent and uncontrollable force. He may remain “radically both natures,” but any “control” is as illusory as for Alex in his “clockwork” state. Both works are profoundly troubling studies of the limits and consequences of human agency

Supplemental Resources

Don Quixote and the Windmills, 1945 - Salvador Dali - WikiArt.org

Danahay, Martin A., ed. Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson. 3rd edition. Broadview, 2015.

McCracken-Flesher, Caroline, ed. Approaches to Teaching the Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, MLA, 2013.

RLS Website. Centre for Literature & Writing, Edinburgh Napier University, 2018

Jekyll Study Questions | Jekyll Literary Analysis Short Research Paper assignment

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

English/Composition Studies

Psychology

Philosophy & Religion

Page Contributor