I had become a problem to myself, asking my soul again and again ‘Why are you downcast? Why do you distress me?’ But my soul had no answer to give.

Saint Augustine

Confessions

Saint Augustine

There is an astonishing number of translations of Augustine’s Confessions into English. The beauty and the innovative character of the work, in addition to its seminal importance in disciplines including theology, philosophy, psychology and literature seem to make it irresistible to translators. The Penguin edition, translated by Gary Wills, is inexpensive and easily accessible, and generally a good choice. Multiple versions are available for free online, including this good recent version by Albert Outler.

Confessions is autobiography, philosophical treatise, psychological study, scriptural interpretation, sermon and prayer.

It is difficult even to state a genre for this work, much less to summarize it. Confessions is autobiography, philosophical treatise, psychological study, scriptural interpretation, sermon and prayer. Students will notice immediately that the text is addressed to God, as a prayer and a confession. We, as readers, are invited to listen in but we are not the primary audience. Later in the work Augustine will begin to address his readers directly, accomplishing the literary equivalent of breaking the fourth wall by occasionally drawing us into community with him and other readers – asking us to pray, and praise, along with him. Interwoven with the prayer and praise is a Augustine’s personal story. He is born the son of a Christian mother and non-Christian father in northern Africa (modern-day Algeria) in the 4th century CE, under the rule of Rome. A precocious child and talented young man, he moves from Africa to Rome to take up a prestigious position as a professor of rhetoric. His life is complicated by at least two desires: by a desire, awakened in him as a tions, most notably Manichaeism and Neo-Platonism, but he can never forget the name of Christ and the influence of his mother, Monica. Finally, he moves with friends away from the distractions of Rome so that they may seek Truth together, and eventually converts to Christianity. He brings his mother to live with een when he read a book by Cicero, to know Truth – and also by consuming sexual desire, which he discusses frankly and openly. As he struggles with himself, he experiments with a number of different religious and philosophical tradithim and his friends until her death. The book ends with powerful reflections on the nature of memory and time that have reverberated through centuries of western thought, and finally with an interpretation of the beginning of the book of Genesis.

Why This Text is Transformative?

...students are immediately drawn to the beauty of the book as a work of literature, and to the intense self-examination it models.

Although much of the narrative of the Confessions happens during Augustine’s time in Italy, this book, so undeniably central to the western canon, is by a writer who was born, grew up, and spent the majority of his career in, Africa. Thus it challenges our conception of where such books originate and our preconceptions about the people who wrote them. It is often called the first autobiography, and presents a remarkable exploration of interiority – questions about the nature of the self, the will, the memory, the intellect, and the soul are central to Augustine’s investigations. Some students are immediately drawn to the beauty of the book as a work of literature, and to the intense self-examination it models. For others, though, it can be difficult initially to approach Augustine’s story presented as a confessional prayer. This difficulty becomes an opportunity if made explicit as a question. What are the implications of reading a text that is presented to us as an exploration of the self before God? How might it be different if the same story were presented as a more traditional narrative? The story of Augustine’s early life, which occupies the first 9 of the 13 books, is fascinating. Augustine tells us of his childhood, his schooling, his friendships, his pride at his academic accomplishments and struggles with what he sees as naive belief, his relationship with sex, his love of the theatre and rhetoric, and his attempts to understand who he is in himself and in relation to God though all that is happening in and around him. Books 10-13, on memory, time, and scriptural exegesis, are important touchstones for many later philosophical thinkers but are certainly less accessible.

A Focused Selection

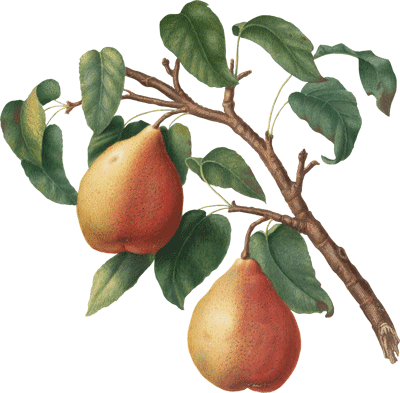

The best-known episode from Augustine’s youth is an excellent starting point through which to approach this work. In Book 2 Augustine tells of how he and his friends, after playing late in the streets, went to the property of a neighbor and stole pears from a large pear-tree. The pears were particularly appealing to look at or good to eat, and in fact the boys ended up throwing them to the hogs. The infraction is in the ordinary course of things a minor one, but Augustine uses it as a vehicle for introspection. What was his motivation for stealing the pears if he didn’t really want them at all? He concludes that he committed the theft not in spite of the fact that he knew it was wrong, but because it was wrong: “It was foul, and I loved it. I loved my own undoing. I loved my error–not that for which I erred but the error itself.”

Study Questions

The pear tree incident raises immediately questions that students have surely encountered in their own lives:

Why do we do things we know to be wrong? Is it true that we can desire an action because it is wrong, rather than for something good that we get from it? If this is true, does it point to something in us that is inherently broken or self-destructive?

As he thinks about the theft of the pears, Augustine considers options in addition to the sheer love of error for its own sake. He realizes that he almost certainly wouldn’t have committed the theft if he had been alone – so what is the role of friendship in the mix of motivations? Why might being in the company of friends make us more likely to act in certain ways, either for good or ill? If the motivation was at least partially the friendship, does that mean that he didn’t love the error for its own sake after all, but for the camaraderie that accompanied it? Or does that mean that they all together loved the error? The theme of friendship is a rich thread to follow through the entire story of Augustine’s early life. The death of a dear friend brings him to despair. It is with a dear friend that he finally converts and gives himself over to God.

From the beginning of the work, and including in connection to the pear tree incident, Augustine speaks of an interior restlessness that pervades his life. He remains dissatisfied despite friendship, notable success in school, an active sex life, etc. Thus he invites us to think about interior dissatisfaction that exists despite external success. Augustine interprets this feeling as a longing for truth, which is in the end a longing for God. How else might one understand it? And finally, the entire work prompts questions about the extent to which we can know ourselves and understand our own motives. How possible is it for us to look at or into ourselves? What might the casting of this work as a confession and prayer to God rather than simply a recounting for the reader bear on this question?

Building Bridges

A Recommended Pairing

The Confessions can be fruitfully brought into conversation with almost any work of autobiography or self-examination, as well as with works of psychology. His influence suffuses Christian theology.

Supplemental Resources

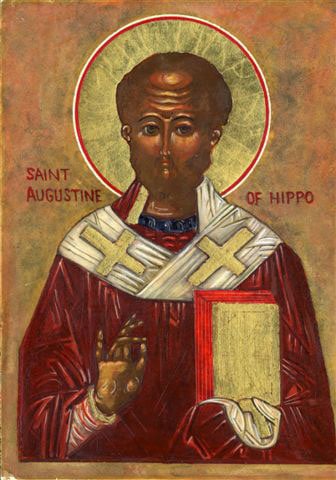

St. Augustine in Christian iconography (churchpop.com)

There are many respresentations of St. Augustine in Christian iconography. He is often presented as dark-skinned. His struggles with sexual temptation are reflected in the song “St. Augustine in Hell,” by Sting. The lyrics include his famous prayer “Make me chaste – but not yet.”

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

English/Composition Studies

Humanities

Sociology

Philosophy & Religion

Page Contributor