He did not want to compose another Quixote—which is easy—but the Quixote itself. Needless to say, he never contemplated a mechanical transcription of the original; he did not propose to copy it. His admirable intention was to produce a few pages which would coincide—word for word and line for line—with those of Miguel de Cervantes.

Jorge Luis Borges

Selected Stories

Jorge Luis Borges

Yates and Irby, ISBN: 978-0811216999

Tlön is a world where the people are idealists in the philosophical sense, they believe that there is no material world, but rather all things are events of a mind (and there is ultimately only one).

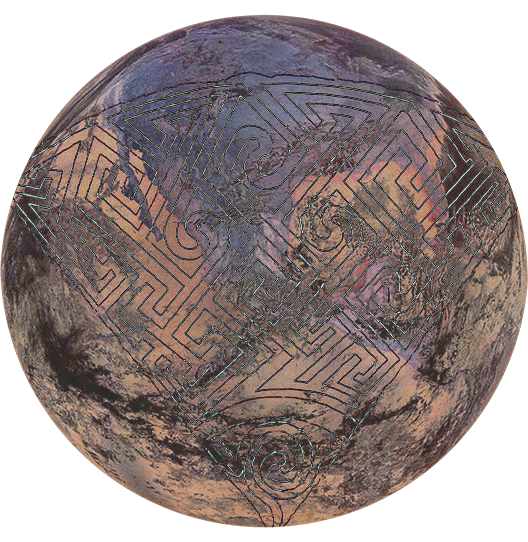

In Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, the narrator and a friend stumble upon a unique encyclopedia that contains an entry on Uqbar, a non-existent country located somewhere between Iran and Turkey. Among the other peculiarities of the inhabitants of Uqbar is that all the literature they produce is about a fictional land called, Tlön. Later the narrator discovers another encyclopedia, but this time entirely dedicated to the strange world of Tlön. Tlön is a world where the people are idealists in the philosophical sense, they believe that there is no material world, but rather all things are events of a mind (and there is ultimately only one). Their languages consist of strings of verbs and adjectives, and they are able to manifest objects known as hrönir. The narrator eventually discovers that the Tlön encyclopedias are the work of a secret society, the Orbis Tertius, whose founder’s goal was “to demonstrate to this nonexistent God that mortal man was capable of conceiving a world” (15). Next, objects from Tlön start making their way into our reality, until, finally, a full set of encyclopedias of Tlön are discovered. Eventually, people are so fascinated with the world of Tlön that they devote all of their energies to discovering and elaborating on it, to the point that the languages and history of the actual world are forgotten.

...Menard undertakes the impossible task of writing Don Quixote, not copying, not writing a version of it, not even rewriting, but writing the text itself.

In Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote, Menard undertakes the impossible task of writing Don Quixote, not copying, not writing a version of it, not even rewriting, but writing the text itself. Over the course of his life he manages to write chapters 9 and 38 of Part 1, and part of 22. At first, Menard attempts to become Miguel de Cervantes, say by learning Spanish and forgetting everything that happened after the 17th century. Later he decides that this is the least interesting of the several impossible ways of carrying out his task. He composes draft after draft following two rules. “The first permits me to essay variations of a formal or psychological type; the second obliges me to sacrifice these variations to the ‘original’ text and reason out this annihilation in an irrefutable manner” (41). All of the drafts are meticulously destroyed by Menard, so there remains only the Quixote.

Borges imagines that the entire universe is a library that consists of all possible books.

In the Library of Babel, Borges imagines that the entire universe is a library that consists of all possible books. He then draws out the intoxicating, enticing, and maddening consequences of this hypothesis

Why This Text is Transformative?

Reading him is like being in an old antique curio shop where you have to go slowly, examining all the unique pieces individually, turning them over to reveal their histories and stories.

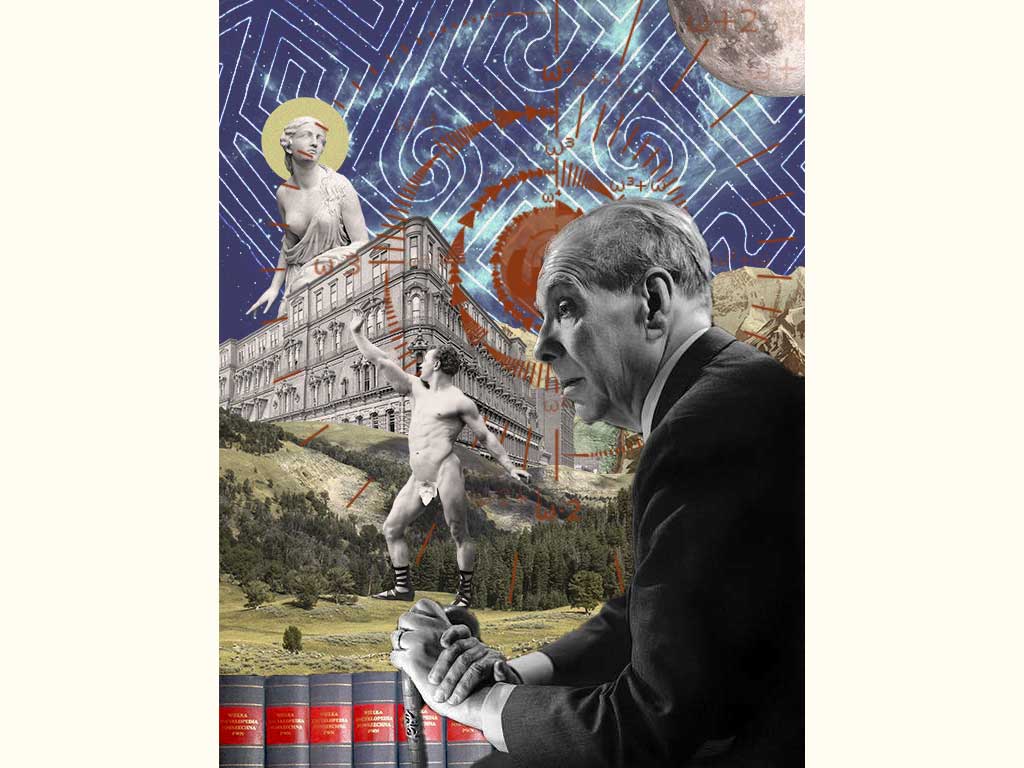

Borges is a writer intoxicated with infinity. He is a writer with secrets buried; you will need to bring a shovel (or the internet). Reading him is like being in an old antique curio shop where you have to go slowly, examining all the unique pieces individually, turning them over to reveal their histories and stories. In a single one of his works he may switch from arcane literary figures, to linguistic theories, to alternate geometries, and back again to heretical theologies. He writes in an almost academic style, and his encyclopedic mind peppers his writing with real sources and references interspersed with fictional ones—making no distinction whatsoever. Anyone interested in infinity, labyrinths, mirrors, esoteric writing, the fine line between fiction and reality, and the porous boundaries of the self will find much treasure in Borges.

A Focused Selection

Study Questions

Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote

In Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote, the narrator claims at the end that Menard’s work has created a new technique of reading: “…this new technique is that of the deliberate anachronism and the erroneous attribution. This technique, whose applications are infinite, prompts us to go through the Odyssey as if it were posterior to the Aeneid and the book Le jardin du Centaure of Madame Henri Bachelier as if it were by Madame Henri Bachelier. This technique fills the most placid works with adventure. To attribute the Imitatio Christi to Louis Ferdinand Céline or to James Joyce, is this not a sufficient renovation of its tenuous spiritual indications?” (44). How can the two techniques of “deliberate anachronism,” so that we imagine Virgil influenced Homer, and “erroneous attribution,” so that we imagine a work was authored by someone other than who it was, change the meaning of a text? What does this feature say about the way we use history and authorship to construct the meaning of a text? If this is a legitimate way of reading, what does this say about authorial intentions? Could one read a text this way without any history or authorship? Why or why not?

Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius

In Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, a secret society unleashes upon the world a fictional world through a series of encyclopedias detailing it. The narrator claims that, “Almost immediately, reality yielded, on more than one account. The truth is that it longed to yield. Ten years ago any symmetry with a semblance of order—dialectical materialism, anti-Semitism, Nazism—was sufficient to entrance the minds of men. How could one do other than submit to Tlön, to the minute and vast evidence of an orderly planet? It is useless to answer that reality is also orderly. Perhaps it is, but in accordance with divine laws—I translate: inhuman laws—which we never quite grasp. Tlön is surely a labyrinth, but it is a labyrinth devised by men, a labyrinth destined to be deciphered by men” (17-18). What is Borges saying about our need for intelligibility here? Does your own need for meaning cause you to deal in fictions at the cost of reality? Is this inevitable? Is it bad? Do you think reality (our universe) is ultimately intelligible? What would convince you one way or the other (i.e., just because we don’t understand some feature of our universe today, doesn’t mean that it will remain unintelligible to us)?

Library of Babel

See if you can calculate, given what Borges tells us, how many rooms the Library, in the Library of Babel, contains. Compare this number to the number of atoms in the universe.

In the Library of Babel, the Library (or Universe) contains all possible books. This sounds like an amazing place to be, until you realize that the chances that you will find yourself in a section of the Library not surrounded by books that are nonsense are vanishingly small. I say that you will be surrounded by books that are nonsense—that is not quite correct, because of course, there are translation manuals in the library that will translate each of those “nonsense” books into any other book there could be. The existential problem for Borges is not how to project meaning onto a meaningless universe, rather it is how to translate meaning from a universe so overflowing with meaning that it threatens to overwhelm with meaninglessness. When we discover or create meaning we answer the question: Why this, rather than that? What happens to this process of meaning-finding-making when in reality every possible event/book exists? How is the universe like a authorless text?

Building Bridges

A Recommended Pairing

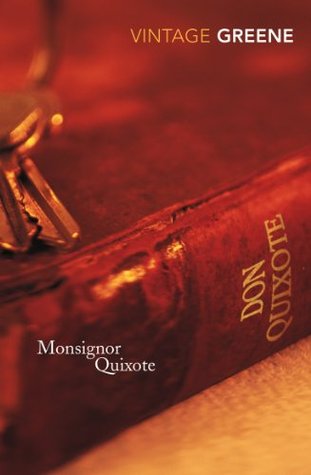

A wonderful short novel by Graham Greene, Monseigneur Quixote, recasts Cervantes’ magnum opus in a way that captures much of the humor and pathos in a more modern context, as the adventures of a Roman Catholic priest and a communist mayor taking to the road together in Spain during the Franco years. The richly imagined characters and their conversations make it clear that the issues that drive Don Quixote’s idealistic quest are not raised only in books of chivalry. How do we live with a commitment to the ideals of a religious faith or a political ideology which, though noble, may not fit easily with and may have unfortunate consequences in the unforgiving world in which we find ourselves? What difference does friendship make in our lives?

Supplemental Resources

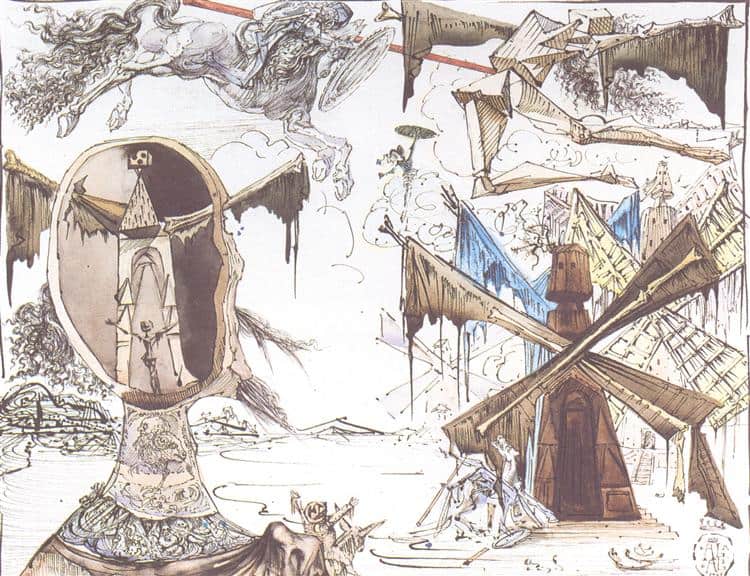

Don Quixote and the Windmills, 1945 - Salvador Dali - WikiArt.org

Don Quixote has been an inspiration for many visual artists. Spanish surrealist Salvador Dali returned to the novel multiple times throughout his long career, creating sketches, paintings, and sculptures of Don Quixote and Sancho, depicting important episodes in the book. A pairing of an episode with one of Dali’s works can lead to a stimulating discussion.

What details do students notice? What do his artistic choices suggest about his interpretation of the characters? To the extent that students are familiar with the story of Don Quixote, it is likely to be as it is filtered through the musical The Man of La Mancha. The musical has its own merits, and is framed by the interesting device of placing Cervantes on stage as a narrator, but of course it is impossible for it to capture much of the complexity of the book – and it alters the ending dramatically. Students may find it interesting to compare the two endings.

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

English/Composition Studies

Humanities

Philosophy & Religion

Page Contributor