[Speaking] is never without fear—of visibility, of the harsh light of scrutiny and perhaps judgment, of pain, of death. But we have lived thorough all of those already, in silence, except death. And I remind myself all the time now that if I were to have been born mute, or had maintained an oath of silence my whole life long for safety, I would still have suffered, and I would still die.

-The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action

Audre Lorde

Poems

Audre Lorde

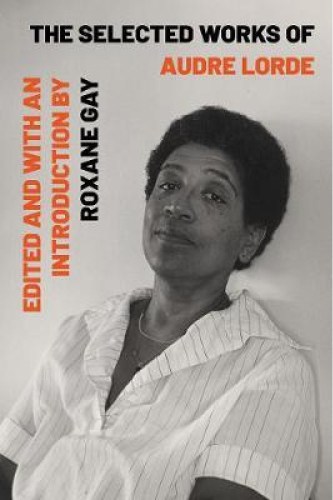

Audre Lorde, Selected Works of Audre Lorde. Ed. Roxanne Gay. Norton, New York

She believed in the connection between written language as it leads to action.

Audre Lorde spoke out. Which might seem an odd thing to say about a writer, but Lorde speaks over and over again about the ways that she is resisting silence: as a Black woman among Black men, as a Black woman among white women, as a lesbian among heterosexuals. Speaking out, keeping herself alive, raising children were all acts of resistance. Her essays speak to anger, strategies for resisting the invisibility she felt because of her race, gender and sexuality, and to ways of living most fully in the world. She believed in the connection between written language as it leads to action. She spoke her truth always and urged other women to speak their truths: “What are the words you do not yet have? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence?” (“Transformation of Silence into Language and Action”). She wrote for herself and she wrote for her communities.

In “Sister Outsider” she writes, “We were born in a poor time/never touching/each other’s hunger.” In this poem, she writes of how individuals living in fear do not thrive: “Now we raise our children/to respect themselves/as well as each other.” In “Chain,” these children become “skeleton children/advancing against us/beneath their faces there is no sunlight/no darkness/no heart remains.” The young girls who “are lying/like felled maples in the path of my feet,” The speaker’s love, her words, bring the skeleton children back to their bodies. Two sisters approach her, whose “father has known/them over and over.” They implore the speaker, “Oh write me a poem mother/here, over my flesh/get your words upon me…oh make us a poem mother/that will tell us his name/in your language.” The girls are able to bear their trauma when the mothers tell their secrets: “what other secrets/do you have to tell me/how do I learn to love her [my child]/as you have loved me?”

In “Power” it is again the children whom she is fighting for:

The difference between poetry and rhetoric

is being ready to kill

yourself

instead of your children.

In the interview between Lorde and Rich, Lorde explains that the poem was written in response to the acquittal of Thomas Shea in Queens after killing 10-year-old Clifford Glover in 1973 by a jury that included 11 white men and one black woman.

She looks at both the power provided to her through her Black community as well as its betrayals:

When you impale me

upon your lances of narrow blackness

before you hear my heart speak

mourn your own borrowed blood

your own borrowed visions

singing through a foreign tongue.

Do not mistake my flesh

for the enemy (“Between Ourselves”)

And what to do with her own rage:

I bend to the knife my ears blood-drumming

across the street my lover’s voice

the only moving sound within white heat

“Don’t touch it!”

I straighten, weaken, then start down again

hungry for resolution

simple as anger and so close at hand

my fingers reach for the familiar blade

the known grip of wood against my palm

I have held it to the whetstone

a thousand nights for this (“Poem for Women in Rage”)

And she celebrates the love she shares with her lover:

Speak earth and bless me with what is richest

make sky flow honey out of my hips

rigid as mountains

spread over a valley

carved out by the mouth of rain.

Throughout her poems and her essays Lorde stays true to exactly the experience she is having in the world. She wants to make the spaces she inhabits better, more inclusive and urges each woman and man to do the work that will make these spaces more equitable, these communities more just.

Why This Text is Transformative?

Lorde was a cultural observer who spoke passionately about the oppressive structures of race, gender, class and sexuality.

Audre Lorde praises, rages, turns a critical eye, desires. The poems are relentless in their observations of Black lives and loves. Lorde was a cultural observer who spoke passionately about the oppressive structures of race, gender, class and sexuality. She articulated the ways that, in the name of sameness, Black women’s experiences were devalued by white women and black men alike and how lesbian sexuality was threatening to both groups and could be used to silence her in both movements. In an interview with James Baldwin, she argued, “We need to acknowledge those power differences between us and see where they lead us. An enormous amount of energy is being taken up with either denying the power differences between Black men and women or fighting over power differences between Black men and women or killing each other off behind them.” She performed similar work in feminist circles. In “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” she argued women could work together only when the deep work of recognition had been done: “As women, we have been taught either to ignore our differences, or to view them as causes for separation and suspicion rather than as forces of change.” She called on white feminists to “reach down into that deep place of knowledge inside herself and touch that terror and loathing of any difference that lives there. See whose face it wears.”

Her poetry was a space for “revelatory distillation of experience…a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action” (“Poetry is Not a Luxury”). Poetry was important because it was a space beyond the strictly rational. Her work speaks of her anger, her frustration, her fears. In “The Uses of the Erotic” she claims that it is our “deepest and nonrational power” that is the source of light we can use for scrutiny of ourselves and our communities: “The erotic is a measure between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings. It is an internal sense of satisfaction to which, once we have experienced it, we know we can aspire. For having experienced the fullness of this depth of feeling and recognizing its power, in honor and self-respect we can require no less of ourselves….The aim of each thing which we do is to make our lives and the lives of our children richer and more possible.”

We read Audre Lorde for the ways “we see her defying [the ideas] of the dominant culture as default,” as Roxanne Gay writes in her introduction to Lorde’s collected work. She continues to be relevant because we continue to struggle in exactly the same ways she spoke out against throughout her fierce body of words.

A Focused Selection

Study Questions

How do you understand Lorde’s project to transform silence? In what ways do you see her poems as a way of speaking her truth and transforming silence? Do you have ways for expressing the truth of your life?

Do you see Lorde’s body of poetry as “revelatory distillation of experience,” as she defines poetry in “Poetry is Not a Luxury”? Why or why not? Cite specific poems.

Read “The Uses of the Erotic” together with her response to criticism brought up in the interview with Adrienne Rich that she is “simply restating the old stereotype of the rational white male and the emotional dark female”: How does Lorde define the erotic? Why is the erotic necessary in her life? What are your thoughts and responses to Lorde’s definition and uses of the erotic? Do you find a sense of the erotic as Lorde defines it in the poems? Which poems? What specifically about the poem makes it seem like it fits Lorde’s definition of the erotic?

What use does Lorde claim for anger in “The Use of Anger”? What provokes her anger? Do you see anger in her poems? Which poems? What specifically about the poem makes it seem like Lorde is expressing her anger? How is she using this anger? What is your response to the anger in the poem?

Building Bridges

A Recommended Pairing

Gloria Anzaldúa

Gloria Anzaldúa: Anzaldúa mestiza consciousness compares to Lorde’s radical feminist identity, wherein they insist on recognizing all aspects of their identities.

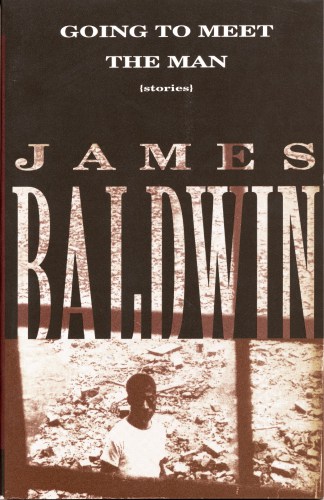

Sonny’s Blues

“Sonny’s Blues” & The Fire Next Time: Baldwin and Lorde both have an eye on the ways Black Americans survive racism. See the interview between them below. In it, Lorde and Baldwin discuss the differences Black men and Black women face and what their responsibilities are to each other.

Supplemental Resources

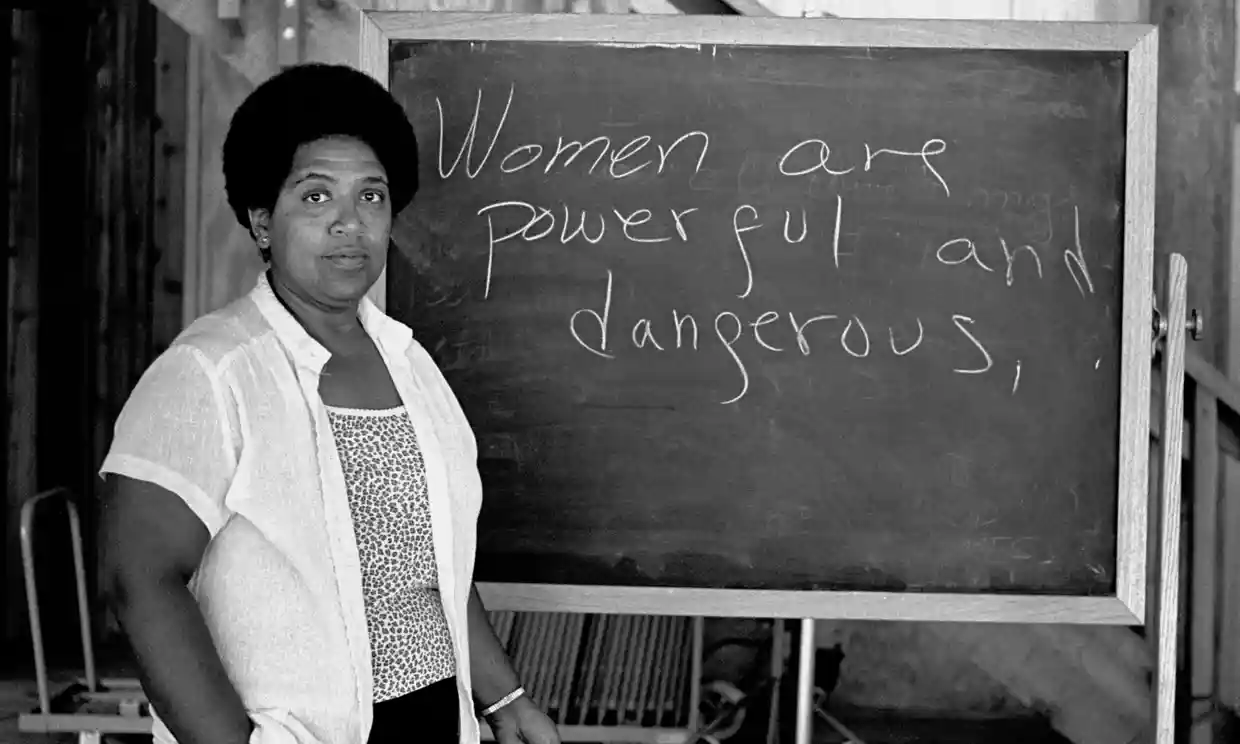

In black and white … Audre Lorde lectures at the Atlantic Center for the Arts in New Smyrna Beach, Florida, 1983. Photograph: Robert Alexander/Getty Images

Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich. “Interview with Audre Lorde.” Signs. Vol. 6, No. 4 (Summer, 1981), pp. 713-736.

“Revolutionary Hope: A Conversation between James Baldwin and Audre Lorde”

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

English/Composition Studies

Humanities

Area Studies

Page Contributor